|

Read Part 1 here.

When you drive, we make really good time. You speed exactly nine miles over the limit because if you are caught going ten miles over, the fine doubles. You hate driving in the east because there are too many cars and the speed limits are too slow, but you love driving in Montana, where you can legally drive as fast as 90 miles per hour. You know when to slow down outside of small towns and cities which often place state troopers a few miles on either side for the first and last exit. I’ve seen you get pulled over before, like that time outside Boise, but you never got a ticket. How do you do that? You picked up a hitchhiker once. This was before I was born, obviously, because you were still a student at Puget Sound and you were driving Brutus back to Tacoma from Colorado after a break. You had told your parents that you would not be alone and that a classmate would be driving with you. But there wasn’t anybody else. At least there wasn’t anybody else until Idaho. You said it was raining and dark. You thought you had seen somebody wet and at the side of the road when you drove by. That’s a human being, you thought. He must be miserable. You doubled back to see if he wanted a lift. You told him to get in the car and he whistled for a wet dripping dog to get out of the ditch in which he was hiding. The hitchhiker apologized and said that he knew that nobody would stop for both him and a wet dog but you interrupted him and told them both to get in the van anyway. May I please take this moment to interject that you would kill me if I picked up a hitchhiker in the rain at night? Especially if I was by myself. Your story is a textbook beginning to a horror movie where you end up dead in a ditch. But you didn’t. In fact, it was lucky that you picked up that hitchhiker. Brutus was rapidly approaching his final days, and he stalled at a rest stop by the border between Idaho and Oregon. The only way to restart the engine was to hold the clutch in while you were rolling. Your hitchhiker had to get out and push Brutus while you popped the clutch. When the engine started and the revived van began to roll away, your hitchhiker had to run to catch you and jump into the moving vehicle, his dog frantically barking in the back. Brutus could barely inch up the steep mountain passes in Oregon but he made the time up on the downhill and probably ended up averaging the speed limit, so that’s what you told the state trooper who pulled you over. Your hitchhiker was in the back of the van packing his pack so he would be ready to get out in a few miles, and when the trooper saw your passenger, he informed you that hitchhiking is illegal in the state of Oregon. “Oh, William and I are old friends,” you lied. And perhaps you were old friends, or you are now, at least. It didn’t matter that his name wasn’t William, or that you would never see him again. He had been there for you, and you for him, and his presence in your own personal mythology now seeps into my own.

0 Comments

This is another essay I wrote in college, but this one is addressed to my mother who is directly responsible for my meanderings. I'll be making my way across New Mexico and the Mojave for the next few days, so settle back and enjoy :)

You gave me a name I had to grow into. To hear you tell it, the genesis for my name came from the Addison & Clarke El stop where you used to get off to see the Cubs play at Wrigley Field. You didn’t live in Chicago for long, nor did you live in Arkansas for long before that. You were born in Morelton, the fourth daughter to a Presbyterian minister who moved you and your sisters out of the South before a southern accent could lay claim to the way you move your tongue. By the time you were seven, your father had moved you again, west this time, to Colorado Springs. Your parents, two native Arkansans, were seduced by the siren song of the mountains during a youth group trip and decided to stay. It was 1970, and they bought the land before there was a house on it. So they built a house. They moved in before they knew there was a church in need of a minister. They call that faith. You inherited your sense of wanderlust from your father and he got his from his mother. You used to spend your summers with your family crammed into an orange Volkswagen Micro Bus named Brutus. Brutus took you through every one of the lower forty-eight states and to each of their capitols. Brutus even took you and your sisters to Juneau, though it never made it to Honolulu. I’ve been to all but seven states.* I know you think some of them don’t count. I haven’t been to all the capitols, and in a few, I’ve only been to an airport, but I count them anyway. I’ve laid eyes on most of America, at least. I drove through many of those states with you. Most of the long trips were with the whole family, but sometimes it was just you and me. Mile after mile, we listened to music, talked, ate Flaming Hot Cheetos and watched our country slip by on long black ribbons of asphalt. You used to tell stories about the trips you took when you were young. Sometimes I forget which stories are yours and which ones are my own inventions. Though the stories themselves haven’t changed in words, as I grow older, age and experience shed light on the reality of your experiences and what they really meant. This is the way it is with children, I suppose. Parents tell them tales, and the child can’t help but make the parent a fearless hero. Adventures are so much grander when the imagination is responsible for filling the gaps in understanding. But with your stories, it’s hard to choose between what’s true and what is true enough. So I search for truth in a series of memories: I return to the road where introspect is inescapable, where silences span miles, where arguments cross state lines, and where experience slides by to a soundtrack of shifting landscapes. *As of June 14, 2022, I have been to all 50 States. A lot has changed since I wrote this. A lot hasn't. People I meet these days don’t really know what to make of me. Whenever I share my story with someone new, I am met with a wide range of reactions, many of which are settled under the umbrella of confusion. Sometimes there is awe. Sometimes there is jealousy. But most people settle on some version of “Have fun while it lasts!” The most common frame of reference people have is of a life tied to responsibility to others, accountability to a mortgage or a landlord, and the expectations of their culture. There is a specific order in which to do things- school, job, marriage, kids, retirement, death with vacations and a few good meals peppered in there. I am not immune to the treadmill of “one thing follows another”, but for the time being, I have stepped off and I have zero interest in getting back on. This is new for me. But I don’t have an answer for the question “What is next?” and I don’t want one.

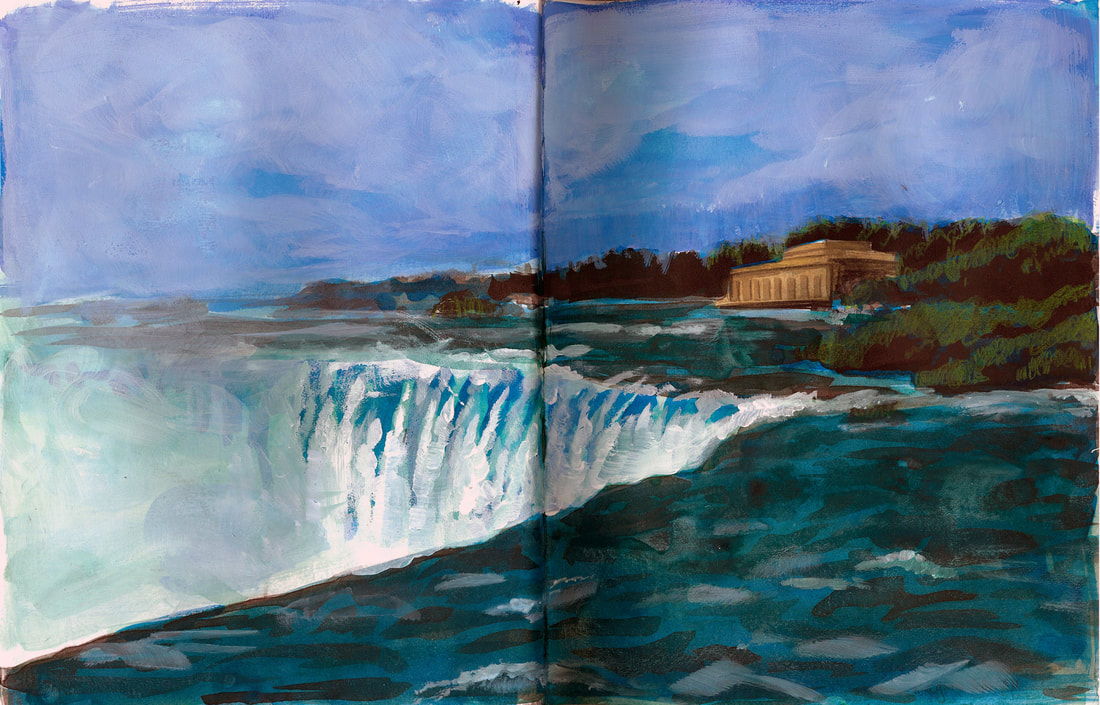

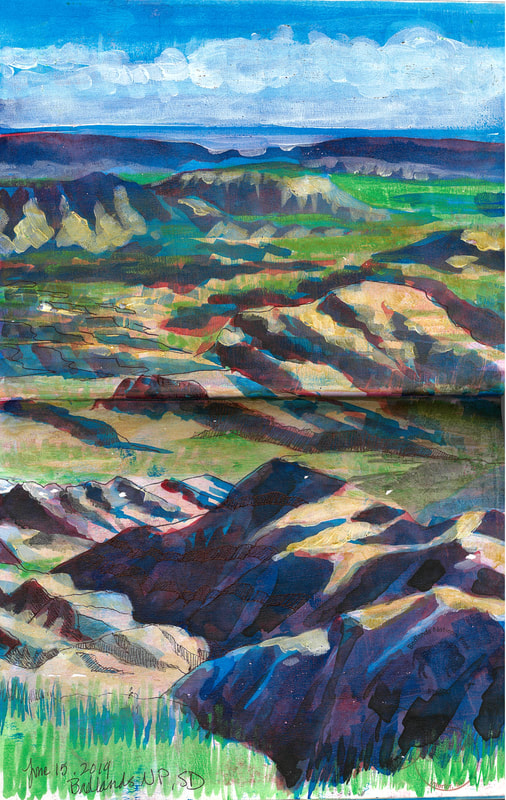

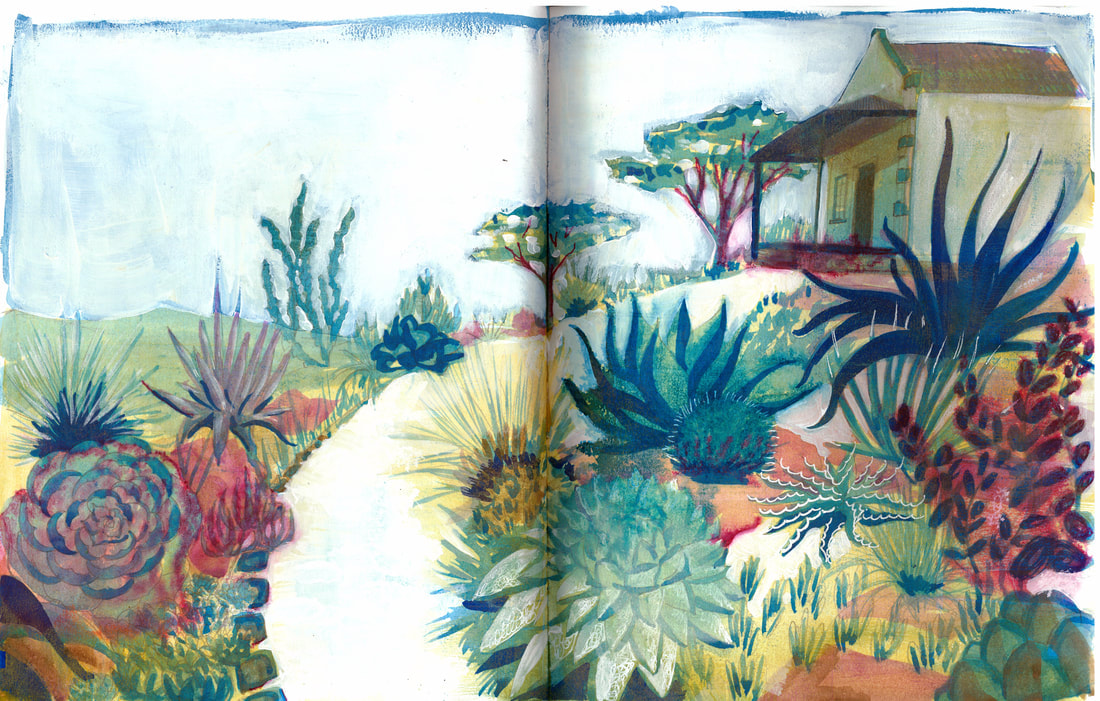

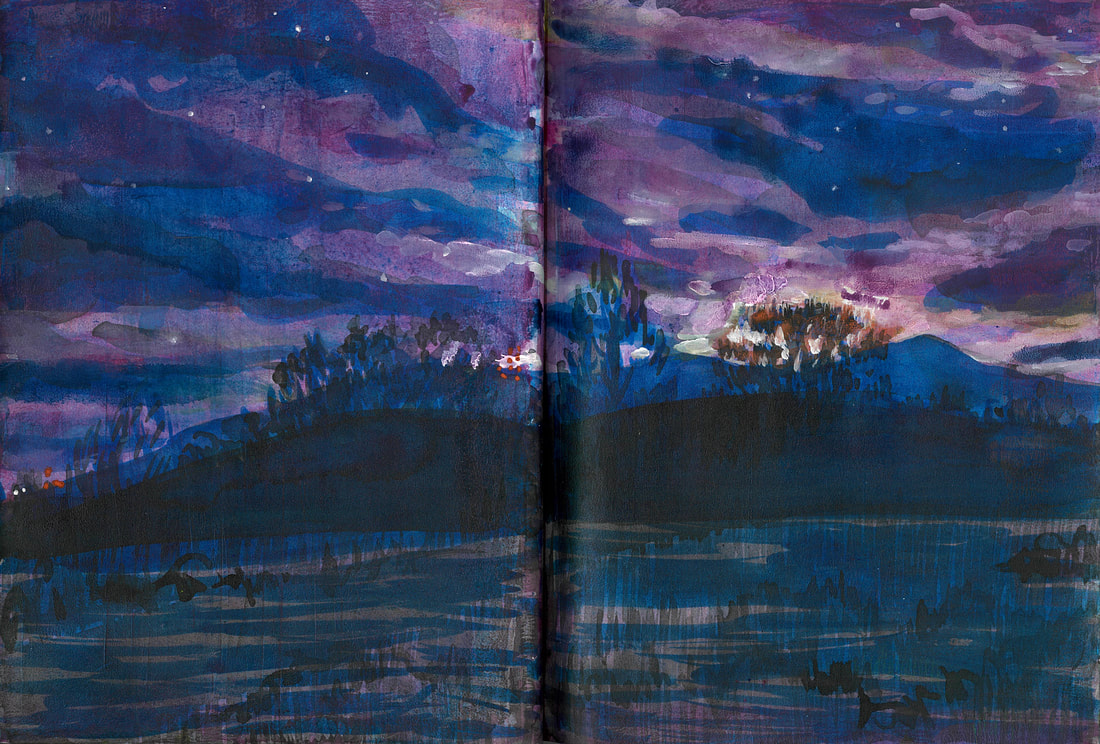

Depending on your perspective, I am either really fortunate or unfortunate to be accountable only to myself. Most days, I feel both ways at the same time. Since my dog died, my only responsibility is to pay my car payment and cell phone bill. All other expenses are optional or the price of living a life. Professionally, I want to make art and write, but I don’t want to be an Artist or a Writer. I often use those labels for simplicity's sake, but those identities are just a portion of my day. Mostly I just want to be known as a good person. Additionally, I’m not trying to find myself. I know who I am and I’m content. What I am trying to do is occupy myself and combat restlessness. Hence the wandering. The thing I like most about myself is that I can talk to almost anyone. I don’t subscribe to the idea that “A stranger is just a friend you haven’t met yet”, but I do feel genuine curiosity when I talk to strangers. Somewhere along the road, I learned how to be charming and trustworthy. I’m interesting but non-threatening, and if I put my mind to it, I can win over even the most anti-social introverts. My AirBnB reviews note that I am sweet and adorable. I regularly get invitations to stay with people who are virtual strangers, and I weirdly trust their intentions more easily than the people who actually know and love me. Those people know that I am sarcastic and somewhat judgmental. The strangers think I’m cute. You meet all kinds of people on the road- The dad towing his family from Minneapolis to San Antonio who invites you to share their picnic, the book store owner who gives you a hug and calls you “Kiddo”, the Lyft driver who gives you her phone number and encourages you to move to Louisiana and teach high school. Some of these interactions turn into important friendships. I met a woman in Amsterdam 14 years ago who I know would put me up on her couch if I showed up in Canada tomorrow. But most of them are temporary and often don’t even end with us knowing each other's name. But as I continue to simplify my life and “bum around” for lack of a better term, I’m thinking more and more about those weak connections and what it takes to trust people to host you and to be worthy of their trust in return. I have the next 6 weeks figured out, but who knows? Maybe someone I haven’t met yet will help me figure out the 6 weeks after that. By the Numbers: 47 pages into the Travel Journal, 3122 miles, 11 states, 8 plein air paintings, 3 AirBnB’s, 1 hotel, 1 glamping tent, 2 friends, 1 cousin, and one great aunt. 2 concerts, 3 crappy sketches of hotels and coffee shops, 2 new stamps for my National Park Passport, 9 books. Day 1- Travel Journal Page 145- Drive from Montgomery Village, MD to Savannah, GA. The drive was less than 600 miles, which in the West means about 9 hrs, but during Spring Break on I-95 amounts to about 11.5 hrs. I saw more cars from New Jersey and New York headed South than from any of the Southern states I passed through. No wonder the South tried to secede from the uppity North. That and the fierce protection of slavery as an institution… Nevermind. I listened to “Women Who Run with the Wolves: Myths and Examples of the Wild Woman Archetype” by Dr. Clarissa Pinkola Estes, which felt insightful and riled me up a bit. There is a romanticization of the life I am currently choosing to lead that brands itself as being “free spirit” and subject to “Wanderlust”. This doesn’t really describe what this lifestyle is like. Yes, it is untethered, but it isn't fully free. Every day isn’t an adventure and barefoot walks at sunset. There is a lot of grit and boredom, asphalt under tires, and bug splatter on the windshield. The “Wild Woman” isn’t your Instagram influencer living van life. She is a woman outside of social norms and suffocated by the expectations assigned to her gender. She also had a traumatic childhood. That wasn’t me. I’m doing this because I can, not because I can’t do anything else. I got to Savannah just as the sun was setting and stayed at the One Way Hotel, a motel decorated with sculptures made from beach trash. I did yoga to release the tension in my back and watched the Avs beat the Stars before going to bed. Day 2- Travel Journal Pages 146-153- Savannah, St. Simons, and Jekyll Island, GA. I packed up quickly and drove into Historic Savannah. I painted Spanish Moss in Ogelthorpe Square and listened to a local tell tourists about his massive white Maine Coon cat, Buddy, who wandered lazily around the square, came when he was called, shook paws, and generally behaved like a dog. On a whim, I messaged a former student of mine who is studying fashion at SCAD, and met her and a friend for coffee near Forsyth Park. I wandered back to the historic district, only to find out I had misplaced my car and searched for it for an additional hour before finally finding it and driving to the coast. I checked into my AirBnB, and left immediately to go out to St. Simons Island to the fishing pier to watch the tankers and absorb the wonderful southern accents. I dipped my feet in the Atlantic and watched my sandal nearly float away before checking Instagram and seeing a suggestion from a friend to go out to Driftwood Beach on Jekyll Island. In spite of the relentless no-see-ums, the trip was worth it to see the dead alien-like forest. I made it back to my AirBnB late, made a pot of ramen and then crashed for the night. Day 3- Travel Journal Pages 154-158- St. Simons Paddle and Drive to Orlando, FL Seventeen years ago, I did a week-long kayaking trip along the Satilla River and out to Cumberland Island, GA. It remains one of my favorite travel experiences, so I looked up the company, which is based out of St. Simons, and booked a 2 hour paddle. The company, Southeast Adventure Outfitters, no longer does those epic trips, but they offer many group paddles half-day, and I shared the experience with a retired couple from Rochester NY, and a family of eight who shared tandem kayaks with a parent and a child in each. The day was lightly breezy, which kept the bugs at bay, and we saw lots of birds, sharks, and spitting oysters. I’m a strong paddler, so I went ahead with one of the guides, Katie, who chatted happily with me about the challenges of being a woman guide as well as a working artist. I learned that Manatees love fresh water, and that it is illegal to spray them with hoses, even if they love it. I took 10 minutes to sketch the marsh before hopping into my car and driving to Orlando where I would stay with my Cousin Leah, and her family. The drive was uneventful. Day 4- Travel Journal Pages 158-163- Winter Park, FL Leah and I dropped the boys off at school and then she took me on a drive around Winter Park to see all the places where she grew up. We stopped for brunch and talked about our families, wandered around book stores and sampled artisan olive oils. We spent the rest of the morning looking at the exquisite Tiffany Glass collection at the Morse Museum of American Art before heading back to the apartment to work and unwind. I finished the painting from the marsh the day before and continued to reconnect with family I hadn’t seen in years. Days 5 to 8- Travel Journal Pages 164-167 Ft. Myers, FL I spent these days staying with my Great Aunt Mary, whom I had spent all of last October with after Hurricane Ian. In the spreadsheet of this trip that outlines the logistics of where I will be, and my expenses and income, I have a few stops that are meant as times to take a breath. Ft. Myers and time with Mary was one of those. We visited and talked about current events and the merits of digital art vs. traditional mediums. I worked at the public library on a design for a mural that would go in a grocery store in Kansas, I did laundry, and I went to the beach. There are plenty of things to do along the gulf coast, but I needed the moment to pause and reflect. Mary shared photos and letters to my Great Great Aunt Dit that had been hidden in a secret drawer in the Brower Desk, a handbuilt cherry behemoth that is passed through the family to anyone with the Brower name, and while the secrets I learned in the letters to Diddy are not mine to share, I feel honored to know them. When I painted on the beach overlooking the turquoise gulf, I took time to record the scene directly behind me as well. Ft. Myers is still devastated from Hurricane Ian, so the apartments behind me were gutted and crumbling. Construction buzzed as the buildings were being rebuilt, but the view looking West over the Gulf of Mexico offered no indication of the mess along the coast. I wonder what else I have forgotten about when I failed to record what was behind me Day 9- Travel Journal Pages 168-171- Mobile, AL The drive from Ft. Myers to Mobile, AL was uneventful except for a few miles of white knuckling through heavy rain as I drove north up I-75. The farther north I went, the more the interstate became rolling hills, and I got lost in undulating meditation as I listened to “Fiona and Jane” by Jean Chen Ho. I rolled into Mobile at around 5 pm and parked downtown to stretch my legs before heading to my next AirBnB. It was Easter Sunday, so everything was pretty quiet and deserted, just how I like my cities, and I was charmed by many of the old 2-story buildings draped in flowers and ornate iron work, punctuated by empty lots and store fronts. My cousin Ian loves Mobile, and referred to it as a dumpster full of gems. I think this is a useful description for a lot of American cities, and I wondered how the city changes when the cruise ships are in town, or when it wasn’t a significant Christian holiday. I’d like to go back sometime and see a concert and enjoy more time there. As it was, I enjoyed some decent beignets, and a quiet walk around the Spanish Plaza before turning in for the night at the Springhill Historic House and AirBnB. Day 10- Travel Journal Pages 172-176- Mississippi Gulf Coast and Drive to New Orleans, LA I pulled off the highway and stopped at Gulf Shores National Seashore. Before now, I had been to all 50 states, but I felt like Mississippi had been short changed since we only stopped for gas there when I drove the coast after high school, and I wanted to give it most of the day. The weather was gorgeous, so I painted the bayou from the fishing pier and listened to three fishermen talk shit and pull 30 pounders from the bay. One of the fishermen, a retired cop from Chicago, was really happy to talk to me while I worked, but he and his fellows tried to spook me when I told them I was headed to New Orleans later that day. They told me to pack a knife and a fake purse, and I took their warning with the grain of salt it deserved. Traveling alone is to be in a constant low level state of fight or flight, and I’m always baffled by the people (usually men) who seem to think I am unaware of the threats that go along with being a woman in this world. Granted, I am a white woman in a country that has been designed to protect me, but the dangers are real and I would be wise to recognize them. All this being said, if I allowed this to dictate every one of my actions, I’d never do anything, so I accept the concern of others with love because it is given with love. After painting, I moved on to Biloxi, where I ate shrimp and crawfish and sipped sweet tea before wandering around town and walking the beach where there were Wade-Ins during the Civil Rights era in protest of segregated beaches. I drove along the coast through the rest of Mississippi and noticed a Waffle House every 2 miles. The words of the fishermen weighed on me, so when I rolled into New Orleans around sunset to find my AirBnB in a neighborhood that was convenient to the French Quarter, but full of potholes the size of a Yugo, and historic houses in a wide range or repair, I allowed my unease to overwhelm me. Sometimes, I lean into being naive and ignorant, especially when I travel, and while the place I was staying was safe, bohemian, and charming, I worried that today was the day the bill for my nonchalance would come due and that I would find my car broken into. I spent the night and most of the next day sitting quietly in my room, listening to the occasional arguments from the neighbors and questioning myself. I resolved to not do anything at night and to take a Lyft the mile to Jackson Square, instead of walking. Days 11 and 12- Travel Journal Pages 177-183- New Orleans, LA, French Quarter and Garden District I got over my fear and had two lovely days in New Orleans. I did take a Lyft into town that afternoon and enjoyed walking the streets of the Quarter and eventually trying and failing to paint a jazz band in front of St. Louis Cathedral in Jackson Square. Most of the square was closed in preparation for French Quarter Fest that weekend, but I sat on a park bench and listened happily to the assorted brass instruments, saxophones, and drums as they played classic New Orleans jazz. It was times like these that I am reminded of why I seek the anonymity of music and the crowds that accompany it. The camaraderie of shared experience eased my nerves and I walked back to my AirBnB through Louis Armstrong Park, keeping my head on a swivel, but feeling much more relaxed. I ventured out again that night to see Hovvdy at the Toulouse Theater and enjoyed a serenade by Robert, my Lyft driver, all the way home. The next morning, I walked again to find the streetcar that would take me to the Garden District where I spent the day wandering and painting the old trees and exquisite houses and gardens. People barely batted an eye at me as I sat on the bumpy brick sidewalks and worked in my sketchbook, though plenty of tourists stopped to talk to me. I have one of those faces that invites conversations from strangers, and while many people were curious about me, most preferred to share their own stories, and I was happy to listen while I worked. Traveling/living like this is a bit strange because I don’t have unlimited funds to do whatever I like and I can’t listen to everyone who sends me a recommendation for what to do and where to eat. I’ve said it before, but this isn’t vacation, and I have to find a balance between what is a can’t miss experience and what is sustainable. The work of walking around, recording what I see, and sharing it is my job, but I can’t just move from place to place and skirt the edges of what makes a city special. This is where I wish I had a local guide to help sift through what is sensational and what is essential to a place. If left to my own devices, I don’t always opt for the unique experience and I fall into patterns of comfort. But that is another post for another time Days 13 to 15- Travel Journal Pages 184-186- Dallas, TX The next few days were spent with my friend from college, Natalie, and her husband, Mike. Unlike in NOLA, my friend was an excellent guide who helped curate my experience and cut down on a lot of the stress of deciding what to do with myself, and I was grateful to have the time with a person whose company feels natural no matter how much time has passed. Natalie lives on the 26th floor of an Art Deco building in the Central Business District and I found myself enjoying all of the details of the old skyscrapers and neon lights of the city. I would have never picked downtown on my own, since I gravitate to historic neighborhoods and rural places, so the experience was novel and gave me an appreciation for Dallas that was separate from its notorious traffic. Over the two days I was there, we visited the Dallas Museum of Art, ate excellent pizza at Partenope, breakfast tacos from the corner store, and wandered around the Bishop Arts District. I had Texas BBQ and saw Pedro the Lion perform in Deep Ellum. I visited with old friends. I didn’t write or draw anything. Again, visiting and experiencing the world is often at odds with recording it, but I will continue to endeavor to find the balance. Days 16 to 18- Travel Journal Pages 187-192- Amarillo, TX, to Las Vegas, NM After packing my car for an uneventful and windy drive to dusty Amarillo, Texas, in the Panhandle, I arrived at Mariposa Eco Village, just outside the city. I would stay in a canvas Tentrr “glamping” tent on rocky rangeland that I shared with some cows and a pack of coyotes. I had a queen bed and plenty of blankets, but once the sun went down, there wasn’t much to do except watch the stars and listen to an audiobook. The Eco Village was a nice surprise: remote, artsy, and quiet. I saw one truck, but apart from a few text messages from my host, I had the place to myself. I painted and posted a few pictures to social media and a friend suggested I check out Cadillac Ranch while I was in the area. Amarillo was meant to just be an overnight stop between Dallas and Las Vegas, New Mexico, so I had no plans to explore it. But when my friend in New Mexico told me she had an errand in Albuquerque that would keep her late, I needed to figure out how to mosey before the 3 hr drive. The wind had buffeted the tent relentlessly throughout the night, so I was up with the sunrise. I had a jalapeño bagel with the retirees at Roasters coffee, journaled, and thought about a friend from high school who died nearly 10 years ago. He was one of my first writing crushes. I had one in every writing course I’d had in college–something about talent and watching someone as they read out loud… it was pathological–I’d written him a postcard when he was in the hospital, not long before he died. Feeling morose, I found a nail salon that was open that early and got a manicure and ruminated on the act of killing time. This happens sometimes when I travel. If left to my own thoughts for too long, I start to get agitated. Everything feels heavy, deep and important. Journaling helps. Hands slick with lotion and still fragile shellac, I programmed Cadillac Ranch into Google Maps and drove 2 miles up the highway to the bizarre roadside attraction. Since 1974, people have been invited to park on the frontage road by I-40 and walk 500 yards out into a dusty field to spray paint the 10 vintage Cadillacs that have been partially buried by their hoods in the dirt. The experience is free, but you can buy stickers and a can of paint from a truck near the entrance and the nearly 50 years of built up paint has resulted in colorful and spongy masses that are reminiscent of cave formations. There’s a similar sight in Alliance, NE, called CarHenge, where vintage autos have been stacked in a parody of Stonehenge and I have to hand it to the hippies for creating something weird and wonderful that breaks up the monotony of the barren landscapes. I was charmed, so I went back to my car, grabbed my paints and Crazy Creek and sat there for 2 hours while people painted their names, favorite sports teams, and important dates on the cars. Plenty of people came to chat and share stories about their journeys while I worked. One woman was there to commemorate the 5 year anniversary of her son’s death, and again I thought of my friend. Sunburned, but pleased with my morning, I packed up and drove West. Part 5 is here.

We moved through the miles slowly some days and quickly during others. We met old friends from summer camp, distant relatives, great aunts, grandmothers and grandfathers. We snapped at each other, listened to audiobooks, and ate sunflower seeds. We visited our future college campuses and tried peach ice cream and powdered sugar-covered beignets. We got lost. We took wrong turns. Many of our wrong turns took us through city centers and were costly both in time and in money. Getting caught in traffic or having to pay unnecessary tolls was like instant karmic punishment for our lapses in attention. At these times, I tried to maintain confidence and morale as the navigator by calmly selecting alternate routes from the map in my lap. Occasionally, when we missed the appropriate junction or exit, I didn’t say anything and quietly chose another way rather than telling the driver to turn around. This bit me in the ass a couple of times, the worst one being when we accidentally crossed the Ben Franklin Bridge headed east from Philadelphia into New Jersey. We had meant to circle west around the city to where we would stay with a friend of Kate’s, but the detour into the wrong state forced us to backtrack. It was then that we learned that all bridges into Philadelphia are free to motorists leaving the city, but cost three dollars to cross if you intend to enter the city, and we were left to frantically dig around the car for quarters to pay the toll. Times like these made me feel as though my map had betrayed me. Modern GPS navigation devices have options that allow users to select routes which avoid tolls, and when wrong turns are taken the little dashboard mounted machine reconfigures its directions to calmly redirect the driver and get them back on track. Something in my core rebels against the idea of having a little box tell me where to go and I scoff at my friends who use their Garmins or Tom Toms for trips to the grocery store and other errands. The displays on satellite navigation systems show generic geometric shapes to indicate where you should go and lack the elegance that a map has. A map is both a tool and a piece of art, and offers a sturdier sense of place, so long as you are able to locate your position on it. This can be a daunting task but when you know where you are on a map, you feel grounded, as if you are part of a landscape that is translated perfectly between dimensions. Reliance on a digital landscape on a digital screen denies the user the chance to intuitively choose their own path based on their own sense of direction because they never truly understand where they are. Similarly, online navigation tools like MapQuest and Google Maps allow users to forego maps in favor of listed directions which tell them when to turn left and after what distance to merge right, but which ignore landmarks and other features characteristic to maps or verbal directions. But digital navigation tools continue to evolve to fit how users seek to use them. In 2010, Google unveiled Google Bike, which helps cyclists choose the easiest and safest route to their destination. Google Maps has further developed routes suited for pedestrians, which can be utilized in conjunction with their public transportation feature. No longer is a car required in order to get the most out of digital navigation. Most days, our atlas was enough, and we followed it up the Atlantic, through New England and finally to Vermont, our Northernmost latitude, at which point we turned around. Kate and Figgins left me in DC on the 4th of July and they continued west to Chicago. By the end of the summer, Kate moved to Idaho with her father before attending college at Albion in Michigan. Figgins moved to Arizona with her father before heading off to Smith. I went to American University in Washington DC and we all eventually transferred to different schools. Figgins was the first to leave. She moved back to Colorado after a semester at Smith. I gave American a full year before transferring to Washington University in St. Louis, but Kate almost made it through four years at Albion. She left at the beginning of her senior year, though she never told me why. I found out through a mutual friend that she’s back in Idaho. I hope she’s doing okay. Kate’s Subaru, Antonio, died last year. On facebook, we all mourned his passing. She still has Joanie, though, the dashboard hula dancer. Figgins still has the trip’s road atlas, though it is now four years out of date, and I still don’t have my driver’s license. What I do have now is a phone loaded with Google Earth. It politely asks me if it can use my current location and then accesses my GPS coordinates to show me my position from space. It zooms down through the virtual atmosphere, the image pixilating and then sharpening until it pauses and hovers 200 feet above the roof over my head. "You are here," it seems to tell me, like a big red dot on a map in an amusement park and I get a little vertigo from the picture resting in my palm. But I no longer fantasize about connecting the dots behind me. Where I have been is clear. So instead I hope and wait for the image in my hand to change from “You Are Here” to “Here Is Where You Will Go.” Note: Figgins uses they/them pronouns now, but chose to keep their previous pronouns in this piece to honor and acknowledge who they were then. Read Part 4 here. We left Zoe with her aunt on St. Simon’s Island in Georgia, and continued without her up the coast through Savannah and to the Outer Banks of North Carolina. Many road atlases mark scenic routes by tracing the appropriate roads with a dotted green line, and in the mountains of Colorado, most of the roads are marked this way. Figgins, who had lived all her life in the land-locked mountainous state, had confused the green dotted scenic route with the blue dashed line which delineates an inter-coastal waterway. It was her turn to navigate in North Carolina, and the atlas on her lap showed her the yellow line that she had drawn skipping across open ocean. We searched for the phantom dotted blue road to the islands, driving onto countless hazy peninsulas which thrust out into the Atlantic. After a few hours of driving in circles, we identified the error and located the ferry to Ocracoke Island and made it to our campsite in time to pitch our tents before dark. The Outer Banks of North Carolina loop east out into the Atlantic like a net cast out to catch tuna. Historically, the islands have undulated to and fro, but residential development has attempted to stabilize the sand, and developers struggle to reclaim land which is incessantly battered by wind and sea. The Wright Brothers selected the Outer Banks to attempt the first ever successful airplane flight because of the wind. Their flyer— the bizarre love child of a kite and a bicycle—flew more than a hundred feet over the dunes to where it landed with a thud in the sand. Ironically, there is no commercial airport on the Outer Banks today, so the only way to get there is by car or by boat and often, a combination of the two. The Outer Banks are also known for lighthouses. Each one is more than one hundred and fifty feet tall and features a black and white geometric pattern, the most eccentric of which is the Cape Lookout lighthouse which sports a diamond pattern and looks like a French harlequin. The Outer Banks’ has a few exceptions to the black and white rule, one of which being the stout white lighthouse on Ocracoke Island, which is less assuming than its northern cousins, but which I dragged my friends to, nonetheless. I had remembered this lighthouse from a trip to the islands years before when my family was traveling the opposite direction and I had wanted to see if it lived up to my memory as a landmark of my childhood. The Ocracoke Lighthouse is no longer in use, and like all of the Outer Banks lighthouses, is maintained by the National Park Service. Unlike the others, it does not have a gift shop, nor does it teem with tourists who wait in line for the chance to climb to the top. The Ocracoke lighthouse is chained shut and surrounded by low trees, sea oats, and tiny yellow butter cups. Most of the lighthouses are no longer in use, but in the United States, those that are operational are maintained by the Coast Guard. Traditional lighthouses housed families who were responsible for making sure the light functioned properly so that it could safely guide sailors past hazardous coastlines and through inland waterways to safe harbors. Each lighthouse served as a navigator and had a style unique to the seafaring culture which it protected. The rise of modern electronic navigation systems has made most traditional lighthouses obsolete which, in conjunction with erosion and encroaching seas, threatens their very existence. As a result, the coastal communities which were once protected by these illuminated sentinels now fight to protect and preserve them. One of the fiercest fights fought was for the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse. The lighthouse was commissioned by the U.S. government to protect an area that was known as the “Graveyard of the Atlantic” due to its notorious shipwreck-causing storms and hurricanes. Originally built in 1803 and rebuilt in 1870, the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse is the tallest lighthouse in the United States at nearly 200 feet, a height which is further emphasized by its trademark black and white spiral pattern that twists all the way to its top. The storms which were responsible for the lighthouse’s construction gnawed away at the shore and threatened to consume it, so in 1999 the National Park Service picked the lighthouse up and moved it, inch by inch, half a mile inland. By the time the three of us visited the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse, we had each begun to yearn for some personal space. The morning had been a rough one. I had stepped on a wasp and every step I took seemed to aggravate the burning itch that emanated from the angry red bump on the arch of my right foot. Packing up camp had been unpleasant and difficult in the gusting wind, and Kate had discovered her cell phone had fallen into the cooler full of melted ice and left to soak overnight. Tempers were short, so when we got there, we all went in separate directions. I got in line to climb to the top of the lighthouse, Kate wandered around looking for anywhere her sodden cell phone might receive a signal, and Figgins sat on top of a red picnic table in the pavilion and smoked one of her rationed cigarettes. When we met up again, we found that each of us had voicemail from the Colonel, politely ordering us to check in, or else he would be severely pissed off. Kate finally got through to him and tried to reason that cell coverage was spotty on the islands and that we were not purposefully trying to be difficult. I took the opportunity to call home only to learn that the Colonel had called my parents to see if they had heard from us. Figgins chose not to call anyone. When we got to the car we found that Joanie, the dashboard hula dancer, had wilted in the heat. The sun-baked plastic had softened causing her to lean forward precariously, bending at the knee like a flamingo. The adhesive that affixed her to the dash, threatened to give at any moment, so I pulled the ballpoint from the pages of my journal and wedged it against the AC vent to prop her up. Note: Figgins uses they/them pronouns now, but chose to keep their previous pronouns in this piece to honor and acknowledge who they were then. Part 3 is here. After visiting the caverns, we were to drive south to Fredericksburg, Texas, to stay with my old roommate, Zoe. As the navigator, I looked for routes to avoid backtracking more than twenty miles. I selected a tiny grey road to which we missed the turn and had to reverse down the highway fifty feet. It was then that I learned that little grey roads are actually one lane dirt roads which cast dust over the car like a shroud. We all coughed and struggled to put up the windows while the Subaru bounced and dipped down the road, like a joyful Labrador chasing a moth. We barely made it to Zoe’s before nightfall and we spent the final miles driving through Texas Hill Country while Zoe coached us on the phone through a maze of back country roads, each of us squinting against the twilight to read the road signs. For the next few days, I would relinquish my role as the navigator while Zoe shared her hometown with us. We swam in the Guadalupe River, watched the sunset from the top of another geological point of interest, simply called Enchanted Rock, visited a two thirds scale model of Stone Henge and the heads from Easter Island, and bought Disney Princess Pez dispensers from a candy shop on Main Street. At the same candy shop, I bought a dashboard Hula Dancer for Antonio. Kate named her Joanie. Zoe joined us for the next six states as we made our way east along the Gulf Coast. Kate, Zoe and I all had family members scattered around Louisiana and Florida, so the four of us were spared the pleasure of pitching a tent in the humidity or the rain. Our first stop was in New Orleans, which was still freshly covered in blue FEMA tarps, and where the street signs were still bent in half around the sign posts. This combined with the complex maze of one way streets made finding our way incredibly difficult. After copious amounts of swearing and moments of road rage, we found the house where Zoe’s oldest brother was staying. Zoe’s brother was making the best of the recent hurricane and was busy buying flood-damaged houses to fix up and flip. We slept on the floor in one of his projects which had avoided the worst of the storm surge and broken levies. We spent the next day wandering around the French Quarter, searching for jazz and hiding from the rain. I took pictures with black and white film and when I finally developed it three years later, the expired film caused all the prints to come out grainy except for one. In it, Kate, Figgins and Zoe sit across from me and my camera. We are waiting for beignets at the Café du Monde and Zoe smiles at me, aviator sunglasses perched on the top of her head, her amber freckles pulled tight across her nose and high round cheek bones. Kate pulls a face, her lips puckered and her brow furrowed. Figgins is smiling too, which is rare. She usually ducks out of photos or at the very least obscures her face with a proudly displayed middle finger. In this picture, however, Figgins holds her cheek in her right hand and her left hand hangs limp and relaxed in front of her chin. She seems happy. For Figgins, the trip was her first step toward becoming liberated. In boarding school, she was one of the few hybrid students who resided in the dorms, but whose parents lived just outside the city in Monument. On a good day, her relationship with her mother was strained and her father had moved out of Colorado and to Arizona by the time she graduated. In the fall, Figgins planned to attend Smith, a women’s college which she imagined would suit her intellect and newfound sexuality. On the road, she was a wanderer, drifting from place to place where everyone but the people in the car was a stranger to her. The days we didn’t spend camping we were hosted by my friends and family, or Kate’s, so every person she met was new to her. Figgins’ world was in the West, but she was willing change that. She had a suitcase full of books and a dry bag that she had bought for a kayaking trip to keep her clothes from getting wet. In it, she said she carried everything she needed. The next few days would net us a speeding ticket in Tallahassee, and a quick dip in the Gulf of Mexico. In Florida, there would be more swimming, this time in crystal clear blue springs which had a current so strong we had to drag each other upstream to get back to our car. We would also veg out, watch “Hellboy” and the entire “Blade Trilogy” while eating stale marshmallows and the trail mix that had melted into a solid mass while we were swimming. After Florida, I convinced Kate to depart the interstate in favor of the slower drive up Route 1 which runs parallel to I-95 from Miami to Boston. The time on the highway moved us through small marsh towns surrounded by trees heavy-hung with silky-grey Spanish moss. I preferred the time on the quieter road, but Kate sat in the driver’s seat gritting her teeth while we slowly drove along behind a green pick-up, whose bed was loaded with fishing gear. At the first chance, we got back on the interstate. Note: Figgins uses they/them pronouns now, but chose to keep their previous pronouns in this piece to honor and acknowledge who they were then. Part 3 of 6. Read Part 2 here: Our next stop was Carlsbad Caverns National Park, and I sat in the passenger seat with Figgins’ road atlas closed and in my lap; my finger marked the page for New Mexico. Highway 285 South to Highway 62 West. I mouthed the words, and flipped the atlas open to retrace the route, checking our direction and reminding Kate what signs to look for. Southeastern New Mexico can be disorienting to a trio of Coloradans from the Front Range. Half of Colorado is flat like Kansas, but the other half features the Rocky Mountains. The Front Range is the Easternmost line of blue snowcapped peaks which run from the north and south of the state and serve as a picturesque backdrop to all of the major cities. As a result, the majority of the population orients themselves based on where the mountains are. If the mountains are on your left, then you are headed north. If they lay behind you, then you are headed east, and so on. When there are no mountains, most Coloradans still use landmarks for direction. Later, when I would live in St. Louis, I would base my location off of the Gateway Arch, but my parents’ new home outside of Washington DC left me directionless. Thick forests stifle the roads and hide all landmarks and all of the interstates run in circles leaving me confused and hopelessly turned around. Southwestern New Mexico has the opposite problem. There is nothing to obscure the view, but the land is flat, dry, rocky, and god forsaken until you reach the Guadalupe Mountains. But beneath this arid tedium is one of the wonders of the natural world. Between 4 and 6 million years ago hydrogen-sulfide-rich waters began to migrate through fractures and faults in the limestone bedrock of the Chihuahuan Desert. Sulfuric acid dissolved the limestone along fractures and folds in the rock to form Carlsbad Cavern. Over time, the Guadalupe Mountains uplifted and busted open the cavern, exposing it to the elements for the first time in its geologic history. As a result, airflow and snow melt allowed for what geologists festively call “cave decorations.” Among these decorations are limestone lily pads, robust totem poles, delicate soda straws, and, of course, stalactites. The cavern is the seventh largest in the world and plunges more than 750 feet underground, which is 120 feet deeper than the St. Louis Arch is tall. The cave itself is made up of a number of chambers with such fantastic titles as the “Hall of the White Giant,” the “King’s Palace,” and the haunting “Spirit World.” By the time we visited, I was already confident in my own Atheism, but I was willing to concede a point to those who would label the cavern God’s natural cathedral. There is something undeniably spiritual about the place. The lights illuminating the cave cast a golden glow, like candles on an altar. White stalactites cling to the ceiling like angels, and even the cave itself forms a cross. As I stood by the “Lake of the Clouds” the lowest point in the cave, fighting with my camera to take a decent picture without using the prohibited flash, I found myself overwhelmed and shivering. In the car I would begin to write about the experience, but give up after only a few minutes, writing simply that the cave was inspiring and that I promised to write more on the subject later. Four years have passed and I am still at a loss for what to write. Note: Figgins uses they/them pronouns now, but chose to keep their previous pronouns in this piece to honor and acknowledge who they were then. Part 2 of 6. This was written before I had a smart phone or had even driven my first road trip mile. Read Part 1 here. Before Google, my family relied on road atlases to navigate our summer road trips and for my first road trip alone after I graduated high school in 2006, I would do the same. Four years of boarding school in Colorado Springs, a town without public transportation, had left me without a license and with a reliance on school buses, cabs, and day students with cars for rides to the orthodontist or the movies. My post-graduation road trip would take me through 27 states and over 5,000 miles and my journey would be shared with my friend Figgins, the girl she was secretly in love with, Kate, and Kate’s white Subaru Outback, Antonio. At 18, I was the oldest, and I pretended to be wise, but my age amounted to little more than the ability to buy cigarettes, though I never acted on it. This pissed Figgins off because the self portrait she had designed for herself typically had a cigarette pinched between her forefinger and thumb. But she was seventeen for a few months longer and I refused to buy her a pack because I hated the smell. She had half a pack stashed away which she would carefully ration for use throughout the trip. I didn’t drink, I didn’t smoke, and unlike Figgins, I wasn’t interested in pursuing altered states. But I saw myself as a nomad and subject to a force which had hooked me behind the collarbones, pulling me towards the road with a kinetic energy that entreated me to keep moving. I fantasized about hitchhiking across Canada, meeting interesting people, consuming mileage and devouring the scenery as it flew by. So when Figgins came to me and proposed we spend the summer working on a boat in Greece, I pleaded her down to a month-long road trip in the United States. I was more comfortable in a car in my own country. Anything more would be too much. Kate signed on because Figgins asked her to and I was fine with that. She was barely seventeen but I admired her. To me, she was an old soul. Kate was the daughter of a widowed and retired military man who scared me and whom I privately referred to as “The Colonel.” She had heavy lidded eyes and long elegant fingers that gripped the steering wheel as she leaned forward on the accelerator to overtake a car that dared to obey the speed limit. She reminded me of Lara Croft, from Tomb Raider, a game I never played but liked the look of. She was a badass with a capital “B” and I could see why Figgins had a crush on her. I planned the trip in my grandparent’s living room in Colorado Springs. I used MapQuest to calculate the distance we would drive each day, estimated how much gas we would need, and how much it would cost when split amongst the three of us. I created the itinerary complete with phone numbers, addresses, and campground reservations. When the first itinerary was declared “too vague” by the Colonel, I added ETAs and emergency contact numbers of friends and family within 300 miles of each stop. When there wasn’t anyone available within 300 miles, I made someone up. Copies of the itinerary were sent to our families and our cell numbers were distributed in the hopes that at least one of us would be reachable wherever we were. The plan was to live out of the car. Most nights we would camp in a pair of two-person tents, and alternate nights in the tent alone. We would cook for ourselves on a propane camp stove and eat from a larder of Zatarans beans and rice, Annie’s Mac n’ Cheese, and avocados we had purchased from Wild Oats. We had water bottles full of dish soap and ziplocks filled with powdered dairy creamer, and ate with camping utensils: forks, spoons, and knives that attached to each other with metal rings and that made a clinking noise when you used them. Some nights, we would stay with people we knew. One of the advantages of boarding school was that your friends and family lived all over the country, and in spite of being on the road for nearly a month, we would have to stay in a hotel for only one night. On the way, we would stop at several National Parks and I would get my National Park Passport stamped. I would write about our journey in the Italian leather journal my grandfather had given me and take pictures every day. I chose the states and the stops, and Figgins marked our route in her road atlas, tracing the roads with a yellow highlighter. Our journey was truncated by complications with Kate, and since we were using her car, we were held hostage to her schedule. While Figgins and I planned the trip, Kate was in her sister’s wedding party. When the ceremony was over and the newlyweds safely on their way to their honeymoon, we thought we were good to go. Instead we were delayed by The Colonel’s insistence that the car be serviced before we were allowed to leave and while I recognized the wisdom, with each day gone, a day on my itinerary vanished as well. But anticipation transformed itself into reality and when we finally hit the road, the sky was a clear blue and the highway was vacant—a graduation gift that promised adventure and possibility. Kate drove the first few hours and I sat in the passenger seat. After lunch, we rotated, and I moved to the back seat while Figgins drove and Kate navigated. We listened to The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy on audiobook, so we didn’t talk. At that point we were all brimming with expectation and varying degrees of anxiety. There wasn’t much to say. We spent the first night at Bottomless Lakes State Park near Roswell, New Mexico, which were, in reality, little more than 12 ft deep ponds with an artificial beach and an amphitheater of sandy red cliffs around three sides. I swam out to the middle of the lake and pointed my toes down, threw my hands straight up above my head and sank. I exhaled to aid my descent and my feet found the silty red bottom, kicking up dust in a cloud that obscured my shins and ankles. I looked up at my hands above my head, fingers black in silhouette against the rippling blue sky. I pulled my hands sharply down to my thighs and rocketed up, breaking the surface with a spray of water that temporarily blinded me with flickering flashes of waves and setting sun. After a quick scan of the shore for my friends, I found them clambering up the face of the red cliffs. I swam over to find Kate breaking off rocks, counting the plains of cleavage, holding them up against the sun, and finally bringing them to her lips. “Mmm, salt,” she declared and tossed a chunk to me in the water and handed another to Figgins. Figgins sat on a boulder and licked her piece, quietly tasting it and watching Kate as she climbed higher. To the tip of my tongue, the rock tasted like sweat. Note: Figgins uses they/them pronouns now, but chose to keep their previous pronouns in this piece to honor and acknowledge who they were then. After I graduated high school, I took a month-long 27 State road trip with four friends. I wrote this series about it when I was in college, and only a few years after this trip took place. That was almost exactly half a lifetime ago for me. I'm retracing many of these steps, so I thought I'd share it again while I do the boring stuff like work on a commission at the local public library in Ft. Myers.

|

Addison GreenThe day-to-days of an Itinerant Illustrator Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed