|

Sometimes, we are so worried about perfecting the final product that we never get started. Ask any writer, artist, chef, YouTuber, or other content creator what the key was to their success, and they will most likely tell you that failure and crappy beginnings are the bedrock of their talent. It is important to make the bad things so you can learn to make the good things.

When I share my blog posts, sketches, or my amateur videos, I am aware they could be better. There are clumsy edits, unintelligible lines, and goofy proportions, but I share them anyway as a way to force myself to move on. Keeping the rough stuff hidden, and quietly agonizing over my flaws impedes my progress, and feeds my anxiety that I will never measure up. I ache to make. Even as I'm writing this, I'm thinking about the paintings I could be doing, the table I could be refinishing, the weeds I could be pulling, the laundry I could be folding... (jokes, that laundry is going nowhere!). I am baffled by the people who seem to be constantly occupied and flawless in their presentation. I think quality is important, but mess can be endearing. When it comes to products that people pay for (an online course, a catered meal, wedding invitations), then quality control is obviously important. Being thorough at the beginning will prevent oneself from having to redo work later, and lends the creator credibility. But the free stuff benefits from a little authenticity. As a teacher and as an artist, it can be easy to hide my mistakes and never try to take risks. But I don't. I own up when I screw up, and hopefully my students will too. Failure on a public stage is painful, but if you fail publicly when the stakes are low, take the feedback you get and apply it to bigger and better things, then perhaps your successes will eclipse the failures that came before. That's all I've got this week. Check back next week for something a little bit more coherent.

3 Comments

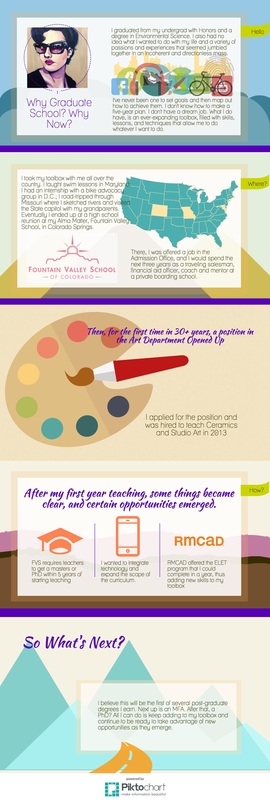

I think in pictures. I remember things in pictures. I understand things in pictures. In Elementary school, I excelled in visual aids. I would spend hours making timelines, collages, and models of the solar system. As an adult, I have absolutely no time for that. Fortunately, there's Piktochart.

Piktochart... is one of the best things to ever happen to me. It looks great, is interactive, and is coherent. It distills information in a way that my visual brain understands and has been invaluable in helping me to analyze the data for my graduate research. Tools like this can help present information online to learners whose eyes may glaze over when they look at tables or paragraphs of information. Check out a gorgeous example below from one of my classes. For a long time, my perceptions of online learning were based on professional development trainings for things like CPR certifications or online Spanish vocabulary quizzes in college. Each course or lesson culminated in a quiz that tested my understanding of the content, and successful completion yielded a certificate certificate or an email to my teacher that I had finished the "tarea".

I usually half-assed these courses, letting the online video play while I was checking Facebook, or skipping the lesson entirely and then just guessing. If I got a question wrong, I would just hit the back button and try again. The problem was that these courses relied on summative assessment, but rather than pushing me to prove what I had learned, they ended up testing what I already knew. The reason why my online masters has been so successful for me is that it has mainly relied on formative assessments that have helped me to build up skills and pieces before turning in the final project or product for each course. I still rely heavily on prior knowledge to get through my assignments (I used to think of this as "bullshitting", but since I have become a teacher, I prefer to think of it as "critical thinking"), but now I am pushed to think more complexly and add to what I know with each step. I think this is the key to meaningful online education. Students cannot be allowed to simply sit through a lesson passively just to check a box so they can move on. It is true that this is important for face-to-face classes as well, but in online programs students rarely interface personally with their instructors, so the instructor never has a chance to observe the student to evaluate their level of engagement. Formative assessments allow for frequent check-ins, and ultimately more engagement for the student. In designing an online course, I would probably do away with online quizzes altogether. Rather, I would challenge each student to come up with a deliverable that demonstrates what they understood. This could be a drawing, an essay, a joke, video, or whatever the student wanted to create that reflects their take-aways. This may take longer than your average quiz, but at least the student would have a portfolio of work they created by the end of the course. |

Addison GreenThe day-to-days of an Itinerant Illustrator Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed