|

Read Part 5 here.

There’s a picture of you and me standing on the balcony at a ranger station on top of a mountain on the Olympic peninsula. The balcony is supposed to overlook the Olympic range with a view of Mt. Olympus and the Puget Sound beyond, but the clouds had rolled in and it was snowing. It was the end of May and I remember being alone up there. No rangers. Just the two of us: our crooked smiles the mirror image of the other’s, our cheeks rosy. My hair was redder than yours, the color chosen from a box from a drug store. Yours also came from a box, but did not quite mask the grey at your temples. I look back at the picture now, but I know now that we couldn’t have been alone. Somebody else must have been there to take the picture. We were there, you and I, because Emma had just graduated with honors from your almost Alma Matter. Emma still had two weeks of training left before Nationals for Division III Crew and she chose to stay with her team in Tacoma. Dad had work, Kiefer had school, and you and I had time to kill. We chose to take the southern route through Port Angeles rather than the northern route by ferry and along the strait of Juan de Fucha. I would have preferred the ferry. There’s something appealing about being in a car on a boat. The Olympic Peninsula is unlike anywhere else in the country with snow-capped mountains surrounded by rain forest and water on three sides. Most of the peninsula is a National Park and inaccessible by car, but we managed to drive out there every summer for most of my childhood to stay in a cabin overlooking the Pacific. When we moved to Maryland, we stopped going. The Northwest was just too far away, I suppose, so I looked forward to going back even if it was only for a night. Sometimes we talk in the car. Sometimes we listen to the radio. When Dad is driving, we listen to country music late at night when we need something ridiculous to keep us awake. The longer road trips require books on tape, but mostly, we listened to CDs. In more than twenty years, the playlist hasn’t changed, though we’ve made an addition or two. Pink Floyd and The Allen Parson’s Project are meant to be played at night on mountain roads, the car’s stereo and the twisting asphalt allows the music to surround you. Certain songs get inextricably paired with certain landscapes, like scent with memory, and my own meanderings with music regularly transport me thousands of miles away to a car with you at its wheel. Conversely, the picture of you and me standing in front of the misty Olympics and the temperate rain forest brings to my mind "Watershed" by The Indigo Girls. Up on the watershed, standing at the fork in the road, You can sit there and agonize until your agony’s your heaviest load. You’ll never fly as the crow flies, get used to a country mile. When you’re learning to face the path at your pace, Every choice is worth your while. That song came on a few miles outside of Olympia, and you burst into tears. It had been a difficult weekend for you. Emma’s graduation was a return to a place you had left, a place that couldn’t handle you, but a place that had fully embraced your eldest child. For you, the University of Puget Sound was a false door. Getting married and having children was not part of the plan. You would have gone into the Peace Corps. You might have majored in archeology. You would have moved to Montreal. But you met my father and you said that after you got married, kids were the next step. I get the idea that you wanted more. You tell me that you have no regrets, and that your greatest accomplishment is your kids and I believe you. But I cannot help but conclude that things should have been different for you. They have to be different for me. Watershed brought you to tears because, with your school behind you and your middle daughter beside you in the rented Chevy which automatically turned the stereo up when it accelerated so that its loud engine wouldn’t drown out the music, the lyrics and the melody were able to replace the turbulence in your mind with clarity and comfort. The relief made you cry. When the song came to the line, “Every five years or so I look back on my life and I have a good laugh…” you grabbed my hand. “I’m sorry,” you told me. I didn’t need your apology. I still don’t. I understand that most of life’s choices aren’t made, they just happen. I graduate from college in fifteen days and with my degree ends the well-paved interstates of my education, and so begin the potholed, unmarked back roads of indecision. So-called “real-life.” There are few road maps and many detours and perhaps the drive is more important than the destination. Doesn’t mean I’m not scared shitless, but with any luck I’ve inherited your sense of direction.

0 Comments

Part 4 here.

Later that summer, you picked me up in Vermont where I was visiting Grandma, and we drove down the coast to Florida with Dad and Kiefer. My two oldest cousins were getting married in Orlando that weekend: one to his middle school sweetheart, the other to the girl he knocked up. We had a few days so we we decided to forego I-95 in favor of a night on Cape Hatteras, on the Outer Banks of North Carolina. We played the Counting Crows and drove down islands so narrow you can see water on either side of the road. Open water makes me nervous, but I love it, like standing at the edge of an escarpment. The sea threatens to consume me like gravity threatens to consume the space I occupy between the ground and the sky. You and Dad spent a lot of time talking about the weddings. Amy and Adam had been dating since they were fourteen, and he proposed to her at your parents’ house at Midnight on the Millennium. David and his pregnant fiancee had been dating only a few months. He was nineteen and she was seventeen. So young. But you were barely seventeen when you met my father in college and he was only twenty. He says he first saw you while you were sitting on a brick wall outside the Sigma Chi fraternity house smoking a cigarette. You wore a white button up shirt, a tapestry skirt and clogs with wooden soles. So young. Dad followed you and Brutus, back to Colorado. You got caught in a blizzard in Idaho, and the snow was so thick that the only clues to where the road went were the tail lights of the car ahead. Brutus’ heater had broken sometime after the 5,000 mile road trip to Alaska, so you drove wrapped up in a sleeping bag. The car in front of you lost its grip and slid off the road, and Brutus slid too when its brakes failed. Dad, in his Subaru, blindly followed your tail lights into a ditch. You were married a few months before you were legally allowed to drink the champagne at your wedding toast. Sixteen years later, we sat on a beach eating pieces of blue crab from the Chesapeake on Trisquits, pretending not to care when the wind blew grains of sand into the open container of crab meat. My shoulders blistered and peeled while my brother’s skin appeared slightly bluish and sickly. The sunscreen that I had neglected to put on but that had diligently been applied to Kiefer’s chest, back, and face was that Coppertone spray kind that would be blue when you put it on so that you could see the spots that you missed. It was supposed to fade away, but never fully did, making him look hypothermic. We were quite the pair, me lobster red, Kiefer frozen blue. We were so young. Part 3 here.

Two weeks after we moved to Kansas City, Missouri, the family loaded into the car and drove back to Colorado for the weekend. Over the next few years, we would make the eight and a half hour drive every other month, and by the time I was in high school, we had memorized that length of I-70. The halfway point is Walkeenee, Kansas, and always has a trooper parked by the westbound exit; the museum in Hayes has a life-like animatronic t-rex which made Kiefer cry; there’s a silo on the Kansas-Colorado Border which informs passersby that “Happiness is a Crock of Beans.” Sometimes, you would wake us up in Colby, Kansas, which is home to a college and a large industrial feed lot. This “Oasis on the Plains” is bookended by two white statues of anatomically correct bulls, complete with low-hanging testicles that stand out against the blue Kansas sky.* One time, you banged on the steering wheel and pointed out that some wise guy had painted the bulls’ scrotums fuchsia. We laughed about that for several miles. There are camels in Kansas, as well. A herd of them. You were the first to see them, and for a long time, you were the only one. They used to graze along I-70 in the eastern part of Kansas which is marginally less flat than the other half and you would often declare, “Camels!” and point emphatically out the window. By the time we looked the camels would be gone. “There are no camels, Mom.” “Yes there are!” “There were never any camels, Mother.” Eventually, you would provide photographic proof that the camels were real, and our game of gaslighting you would end. They were dromedary camels. One hump. Those drives along I-70 cut across Tornado Alley, the flat stretch of country between the Rocky Mountains and the Mississippi River through which tornadoes tear with desensitizing frequency. Sometimes the violent winds would force the van towards the edge of the road and you would fight against it, your forearms flexing and cramping as your hands gripped the wheel to compensate. You called home once when you were making the drive eastbound, and I picked up the phone. I listened to your awe as you sped along the interstate and watched three twisters touch down around you. No rain falls during a tornado so the air is clear enough to see the clouds churn and contort into a funnel which gradually descends from the pewter grey canopy until it finally connects with the earth. Tornadoes have been recorded to span up to two and a half miles across and you estimated yours to be between three and five miles away. You weren’t nervous or scared, just incredibly excited, and I wanted to be there with you. I didn’t ask you to pull over and lay down in a ditch, a strategy given to me by my fifth grade science teacher. I knew tornadoes to be selective in their destruction, leveling one side of a street, while leaving the other side intact. I knew these tornadoes wouldn’t touch you. By the summer I was thirteen, we had been living in Kansas City for nearly three years. Our trips to Colorado were becoming less regular, and Emma and I were finally warming to a few aspects of living in the Midwest. We took sailing lessons on our small lake and learned how to tie knots. We went to soccer camp at KU, and discovered frozen custard. Our proximity to the eastern half of the country led to road trips to Florida and the Northeast. The farther east we went the more densely populated and twisty the states became. Major cities were more frequent, leading us to drive fewer miles but longer hours through thick traffic and low speed limits. We expanded our definition of what a road trip was, and that summer when I was thirteen, we altered it to include the drive between Kansas City and St. Louis—a mere 246 miles—when you and I went to pick Emma up when she flew in from Paris. For you and me, the drive was more important than the destination. I-70 between Kansas City and St. Louis crosses the Missouri River several times which used to confuse me. Rivers are rare in the west and roads hardly ever encounter them, so I had come to associate crossing the Muddy Mo with crossing the state line between Kansas and Missouri. You and Dad used to kiss every time we crossed the border between states, and when I was in the passenger seat, we would blow air kisses. I puckered my lips every time we crossed the river in central Missouri, but my kiss would go undelivered. We listened to Sister Hazel’s album, "Fortress", in the car. The opening track, “Change Your Mind,” was your new anthem, its poppy refrain calling you to change your mind if you are tired of fighting battles with yourself and if you “wanna be somebody else.” The entire album is a reminder to be grateful for what you have and its super saccharine message coupled with the movement of the car seemed to tickle you. During the line “I’ll follow you wherever when you lead me by my nose on another great adventure,” you gently punched my shoulder. “See, that’s like us. I’m leading you by your nose on another great adventure.” You said this with a self-consciousness that you had adopted recently when talking to me, as if you were pleading with me to forgive you for something. You still do it sometimes. I sat with my feet up on the dashboard with my hands pinched between my knees and looked at you through a pair of dark sunglasses. I smiled a small smile and you continued singing along to the song and I watched central Missouri slide by. You liked to plan special stops when we took road trips, a few hours here and there to stretch our legs and learn something. Most trips included pit stops at monuments, historical reenactment sites, battle fields, and occasionally complacency bought by peppermint sticks and rock candy. The drive to St. Louis takes about four hours and my sister wouldn’t land until the next day, so we decided to stop in Fulton, Missouri, to see a section of the Berlin Wall. This sojourn took us off the interstate and onto a State highway, where the speed limit was slower and the scenery was closer to the road. Central Missouri is full of Anytown, U.S.A.s where the cars are old, the Main Street is well manicured and freshly painted, and fences white, and picketed. Fulton appeared to be much of the same, so the twenty four-foot section of the Berlin Wall covered in anti-war graffiti was surprising and out of place. The Wall was part of a sculpture called “Breakthrough” and was given to Fulton to commemorate a post WWII visit by Winston Churchill to the local college. During his visit, the former British Prime Minister delivered his infamous “Iron Curtain” speech where he coined the phrase to describe the division between Western powers and the area controlled by the Soviet Union. The speech marked the onset of the Cold War, and 43 years later, Churchill’s granddaughter, Edwina Sandys would cut two human silhouettes into the wall in a sculpture that would mark its end. The Wall appealed to you for a number of reasons. You were a self-proclaimed “punk rocker with a hippie soul” in your adolescence, and a cold war relic covered with anti-war graffiti spoke to that sensibility. But what really seemed to draw you to Fulton was intellectual starvation. You dropped out of college when the hills and valleys of your depression blurred your academic focus. You were too smart to be left alone with your own mind and for a while your daughters were too young to keep up with you much less challenge you. You hungered for information, especially information that most people knew nothing about. The Berlin Wall in Fulton, Missouri the perfect coalescence of history and random chance, about which most of the country was oblivious. Our trip through Fulton and subsequent attempts to find the interstate again got us lost on dusty roads between bucolic pastures. Rain had battered the Midwest throughout the summer, and the rivers had over-spilled their beds leaving many fields submerged. No rain had fallen in over a week, though, so the roads were dry until they vanished into a premature horizon, the reflections turning farmland into sky. We approached one of these evanescent lakes standing between us and the interstate and drove through slowly. The water rose faster than we expected, reaching our door handles before we had driven 10 feet. We stopped. “Lets go on,” I said, “we can make it.” You looked out at a yellow road sign, its post visible only two feet above the water. “That’s probably only three feet deep,” I urged again. “Let’s do it.” I can’t remember whether we made it through or if we turned back. I only know we didn’t get stuck. *When I wrote this, it was before I had a license and would make the drive across Kansas on my own, so I accidentally combined details about Colby, Oakley, and Hayes, Kansas. To figure out what I got wrong, you'll just have to make the drive yourself! Read Part 2 here.

After you had children, you stopped picking up hitchhikers. I remember you bemoaning your full car once when we passed a father and his two kids sitting with all their ski equipment at the bottom of Berthoud Pass near Winter Park, Colorado. There wasn’t room for them anymore, so you shared the journey with your kids, instead. We have to remember things collectively or else we forget them. We remember serene things, like the sunflowers that pursued the sun as we drove west through Nebraska, their yellow faces turning to watch us go. We remember funny things, like the time when Taj was a puppy, and we were driving through Idaho when he climbed up onto my shoulder only to pee on me and my pillow. We remember scary things, like the time we got a flat in Great Falls, Montana, and we had to change the tire while daylight edged away. But neither one of us can remember why we were in Seattle that October. We used to visit Washington every summer but the trip to the Northwest in the fall was unusual. We know it was October because I was ten years-old, and in a month, I would turn eleven, and three days after that we would move from Denver to Kansas City. Emma and Dad had to fly home early leaving me, you, and Kiefer, who must have been only two years-old, to drive back. We knew this drive two ways: We usually took the northern route through Eastern Washington and the neck of Idaho, in and out of a number of identical valleys in Montana, until we had to drop south through Wyoming. The southern route was the one you took with your hitchhiker through Oregon and Southern Idaho and that swung south and then east through Utah. This time, we decided to take the northern route but we would drive most of the way the first day so we could take an extra day to see Yellowstone National Park. We did the things you do when you go to our Nation’s first National Park. We waited and watched Old Faithful erupt, saw the 30 minute documentary in the visitor’s center, and bought a Wyoming state pin to add to my collection. I remember the geyser being smaller than I thought it would be. We had to stand 100 feet away behind a low wooden fence. A park ranger told the crowd that it was a cone geyser that shoots 240 degree water 180 feet into the air every 90 minutes. I thought about how hot that water was and tried to imagine what the pain would feel like if I touched it. We piled back into the car and drove into the heart of the park to Mammoth Hot Springs. The hotel there was built early in the century a short walk from the hot springs which got their name from a mountain that looked more like a sleeping bear than an ancient elephant. A heard of elk grazed in front of the hotel while you checked us in. A bull elk’s bugle resonates like a scream of terror and carries on the wind like a sound effect from a bad horror movie. While you were inside at the front desk, Kiefer and I walked hand in hand across the dead grass towards the elk. We stopped thirty feet away from the herd and the harem ignored us, but the bull raised his head periodically to issue a bleat which rent the otherwise silent scene. We turned back to the car and saw you standing on the veranda of the hotel watching us. Later you would tell me that if the bull elk were to charge, you knew I would have thrown myself in the way to protect my brother. The thought hadn’t occurred to me and made me uneasy. You didn’t sleep well that night. You never seemed to get much sleep when we were on the road and we regularly piled into the car at daybreak in an attempt to satisfy your itch to get moving. You put us into the car early the next morning, before the Park could emerge from the fog that had settled during the night. The road was narrow and winding, but you are an excellent driver. Your sense of direction is uncanny, and you are at ease behind the wheel in almost all conditions. We cut through the mist and you showed me why it is dangerous to drive in fog with the brights on. You briefly switched on the high beams and a wall of white collided with the car. You flicked them off, and ghostly aspens emerged through the fog and we could see more of the road in front of us. As the road gently curved, you showed me the effect again and the trees disappeared once more. By the time the sun had burned away most of the moisture, fatigue had caught up with you and we stopped in the parking lot of one of the geothermal points of interest. You told me to go ahead on my own along the path to see the boiling, dove grey mud pots and cobalt basins, while you stayed in the car with my sleeping brother. I wasn’t gone long. I practically skipped along the boardwalk that traversed the cracked and buckled earth. The colors there spanned the whole spectrum, and yellow sulfur bubbled and fizzed around the pillars of the boardwalk, supplying the air with the stench of rotten eggs. I walked the entire loop in fewer than ten minutes, bypassing elderly couples and bus loads of tourists. I didn’t want to be alone for long. Read Part 1 here.

When you drive, we make really good time. You speed exactly nine miles over the limit because if you are caught going ten miles over, the fine doubles. You hate driving in the east because there are too many cars and the speed limits are too slow, but you love driving in Montana, where you can legally drive as fast as 90 miles per hour. You know when to slow down outside of small towns and cities which often place state troopers a few miles on either side for the first and last exit. I’ve seen you get pulled over before, like that time outside Boise, but you never got a ticket. How do you do that? You picked up a hitchhiker once. This was before I was born, obviously, because you were still a student at Puget Sound and you were driving Brutus back to Tacoma from Colorado after a break. You had told your parents that you would not be alone and that a classmate would be driving with you. But there wasn’t anybody else. At least there wasn’t anybody else until Idaho. You said it was raining and dark. You thought you had seen somebody wet and at the side of the road when you drove by. That’s a human being, you thought. He must be miserable. You doubled back to see if he wanted a lift. You told him to get in the car and he whistled for a wet dripping dog to get out of the ditch in which he was hiding. The hitchhiker apologized and said that he knew that nobody would stop for both him and a wet dog but you interrupted him and told them both to get in the van anyway. May I please take this moment to interject that you would kill me if I picked up a hitchhiker in the rain at night? Especially if I was by myself. Your story is a textbook beginning to a horror movie where you end up dead in a ditch. But you didn’t. In fact, it was lucky that you picked up that hitchhiker. Brutus was rapidly approaching his final days, and he stalled at a rest stop by the border between Idaho and Oregon. The only way to restart the engine was to hold the clutch in while you were rolling. Your hitchhiker had to get out and push Brutus while you popped the clutch. When the engine started and the revived van began to roll away, your hitchhiker had to run to catch you and jump into the moving vehicle, his dog frantically barking in the back. Brutus could barely inch up the steep mountain passes in Oregon but he made the time up on the downhill and probably ended up averaging the speed limit, so that’s what you told the state trooper who pulled you over. Your hitchhiker was in the back of the van packing his pack so he would be ready to get out in a few miles, and when the trooper saw your passenger, he informed you that hitchhiking is illegal in the state of Oregon. “Oh, William and I are old friends,” you lied. And perhaps you were old friends, or you are now, at least. It didn’t matter that his name wasn’t William, or that you would never see him again. He had been there for you, and you for him, and his presence in your own personal mythology now seeps into my own. This is another essay I wrote in college, but this one is addressed to my mother who is directly responsible for my meanderings. I'll be making my way across New Mexico and the Mojave for the next few days, so settle back and enjoy :)

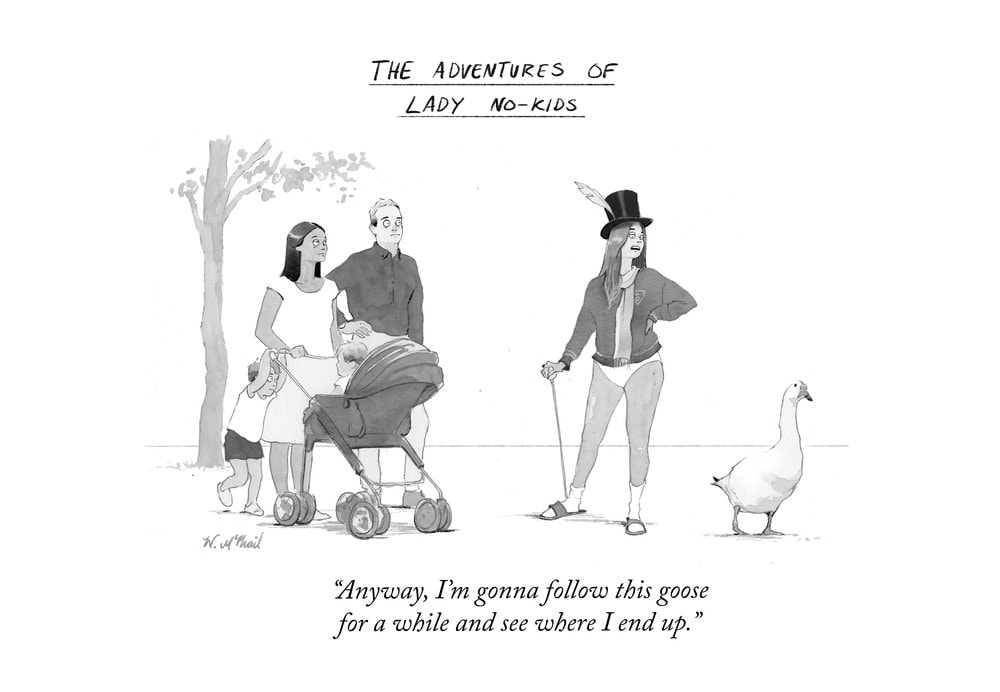

You gave me a name I had to grow into. To hear you tell it, the genesis for my name came from the Addison & Clarke El stop where you used to get off to see the Cubs play at Wrigley Field. You didn’t live in Chicago for long, nor did you live in Arkansas for long before that. You were born in Morelton, the fourth daughter to a Presbyterian minister who moved you and your sisters out of the South before a southern accent could lay claim to the way you move your tongue. By the time you were seven, your father had moved you again, west this time, to Colorado Springs. Your parents, two native Arkansans, were seduced by the siren song of the mountains during a youth group trip and decided to stay. It was 1970, and they bought the land before there was a house on it. So they built a house. They moved in before they knew there was a church in need of a minister. They call that faith. You inherited your sense of wanderlust from your father and he got his from his mother. You used to spend your summers with your family crammed into an orange Volkswagen Micro Bus named Brutus. Brutus took you through every one of the lower forty-eight states and to each of their capitols. Brutus even took you and your sisters to Juneau, though it never made it to Honolulu. I’ve been to all but seven states.* I know you think some of them don’t count. I haven’t been to all the capitols, and in a few, I’ve only been to an airport, but I count them anyway. I’ve laid eyes on most of America, at least. I drove through many of those states with you. Most of the long trips were with the whole family, but sometimes it was just you and me. Mile after mile, we listened to music, talked, ate Flaming Hot Cheetos and watched our country slip by on long black ribbons of asphalt. You used to tell stories about the trips you took when you were young. Sometimes I forget which stories are yours and which ones are my own inventions. Though the stories themselves haven’t changed in words, as I grow older, age and experience shed light on the reality of your experiences and what they really meant. This is the way it is with children, I suppose. Parents tell them tales, and the child can’t help but make the parent a fearless hero. Adventures are so much grander when the imagination is responsible for filling the gaps in understanding. But with your stories, it’s hard to choose between what’s true and what is true enough. So I search for truth in a series of memories: I return to the road where introspect is inescapable, where silences span miles, where arguments cross state lines, and where experience slides by to a soundtrack of shifting landscapes. *As of June 14, 2022, I have been to all 50 States. A lot has changed since I wrote this. A lot hasn't. People I meet these days don’t really know what to make of me. Whenever I share my story with someone new, I am met with a wide range of reactions, many of which are settled under the umbrella of confusion. Sometimes there is awe. Sometimes there is jealousy. But most people settle on some version of “Have fun while it lasts!” The most common frame of reference people have is of a life tied to responsibility to others, accountability to a mortgage or a landlord, and the expectations of their culture. There is a specific order in which to do things- school, job, marriage, kids, retirement, death with vacations and a few good meals peppered in there. I am not immune to the treadmill of “one thing follows another”, but for the time being, I have stepped off and I have zero interest in getting back on. This is new for me. But I don’t have an answer for the question “What is next?” and I don’t want one.

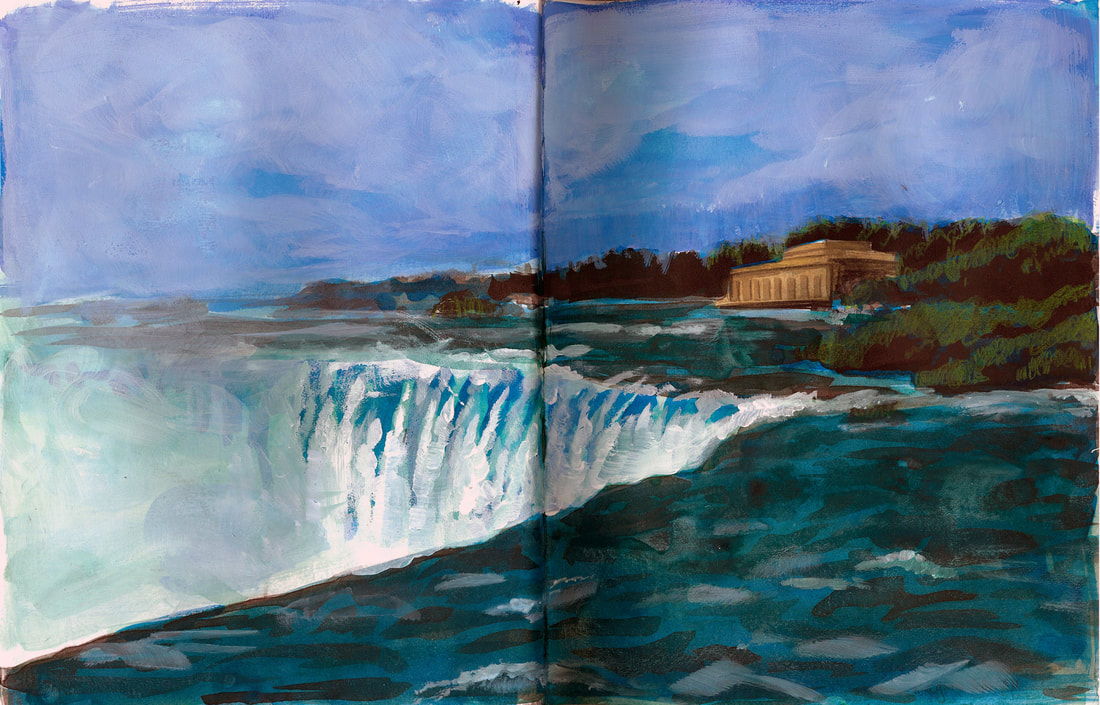

Depending on your perspective, I am either really fortunate or unfortunate to be accountable only to myself. Most days, I feel both ways at the same time. Since my dog died, my only responsibility is to pay my car payment and cell phone bill. All other expenses are optional or the price of living a life. Professionally, I want to make art and write, but I don’t want to be an Artist or a Writer. I often use those labels for simplicity's sake, but those identities are just a portion of my day. Mostly I just want to be known as a good person. Additionally, I’m not trying to find myself. I know who I am and I’m content. What I am trying to do is occupy myself and combat restlessness. Hence the wandering. The thing I like most about myself is that I can talk to almost anyone. I don’t subscribe to the idea that “A stranger is just a friend you haven’t met yet”, but I do feel genuine curiosity when I talk to strangers. Somewhere along the road, I learned how to be charming and trustworthy. I’m interesting but non-threatening, and if I put my mind to it, I can win over even the most anti-social introverts. My AirBnB reviews note that I am sweet and adorable. I regularly get invitations to stay with people who are virtual strangers, and I weirdly trust their intentions more easily than the people who actually know and love me. Those people know that I am sarcastic and somewhat judgmental. The strangers think I’m cute. You meet all kinds of people on the road- The dad towing his family from Minneapolis to San Antonio who invites you to share their picnic, the book store owner who gives you a hug and calls you “Kiddo”, the Lyft driver who gives you her phone number and encourages you to move to Louisiana and teach high school. Some of these interactions turn into important friendships. I met a woman in Amsterdam 14 years ago who I know would put me up on her couch if I showed up in Canada tomorrow. But most of them are temporary and often don’t even end with us knowing each other's name. But as I continue to simplify my life and “bum around” for lack of a better term, I’m thinking more and more about those weak connections and what it takes to trust people to host you and to be worthy of their trust in return. I have the next 6 weeks figured out, but who knows? Maybe someone I haven’t met yet will help me figure out the 6 weeks after that. By the Numbers: 47 pages into the Travel Journal, 3122 miles, 11 states, 8 plein air paintings, 3 AirBnB’s, 1 hotel, 1 glamping tent, 2 friends, 1 cousin, and one great aunt. 2 concerts, 3 crappy sketches of hotels and coffee shops, 2 new stamps for my National Park Passport, 9 books. Day 1- Travel Journal Page 145- Drive from Montgomery Village, MD to Savannah, GA. The drive was less than 600 miles, which in the West means about 9 hrs, but during Spring Break on I-95 amounts to about 11.5 hrs. I saw more cars from New Jersey and New York headed South than from any of the Southern states I passed through. No wonder the South tried to secede from the uppity North. That and the fierce protection of slavery as an institution… Nevermind. I listened to “Women Who Run with the Wolves: Myths and Examples of the Wild Woman Archetype” by Dr. Clarissa Pinkola Estes, which felt insightful and riled me up a bit. There is a romanticization of the life I am currently choosing to lead that brands itself as being “free spirit” and subject to “Wanderlust”. This doesn’t really describe what this lifestyle is like. Yes, it is untethered, but it isn't fully free. Every day isn’t an adventure and barefoot walks at sunset. There is a lot of grit and boredom, asphalt under tires, and bug splatter on the windshield. The “Wild Woman” isn’t your Instagram influencer living van life. She is a woman outside of social norms and suffocated by the expectations assigned to her gender. She also had a traumatic childhood. That wasn’t me. I’m doing this because I can, not because I can’t do anything else. I got to Savannah just as the sun was setting and stayed at the One Way Hotel, a motel decorated with sculptures made from beach trash. I did yoga to release the tension in my back and watched the Avs beat the Stars before going to bed. Day 2- Travel Journal Pages 146-153- Savannah, St. Simons, and Jekyll Island, GA. I packed up quickly and drove into Historic Savannah. I painted Spanish Moss in Ogelthorpe Square and listened to a local tell tourists about his massive white Maine Coon cat, Buddy, who wandered lazily around the square, came when he was called, shook paws, and generally behaved like a dog. On a whim, I messaged a former student of mine who is studying fashion at SCAD, and met her and a friend for coffee near Forsyth Park. I wandered back to the historic district, only to find out I had misplaced my car and searched for it for an additional hour before finally finding it and driving to the coast. I checked into my AirBnB, and left immediately to go out to St. Simons Island to the fishing pier to watch the tankers and absorb the wonderful southern accents. I dipped my feet in the Atlantic and watched my sandal nearly float away before checking Instagram and seeing a suggestion from a friend to go out to Driftwood Beach on Jekyll Island. In spite of the relentless no-see-ums, the trip was worth it to see the dead alien-like forest. I made it back to my AirBnB late, made a pot of ramen and then crashed for the night. Day 3- Travel Journal Pages 154-158- St. Simons Paddle and Drive to Orlando, FL Seventeen years ago, I did a week-long kayaking trip along the Satilla River and out to Cumberland Island, GA. It remains one of my favorite travel experiences, so I looked up the company, which is based out of St. Simons, and booked a 2 hour paddle. The company, Southeast Adventure Outfitters, no longer does those epic trips, but they offer many group paddles half-day, and I shared the experience with a retired couple from Rochester NY, and a family of eight who shared tandem kayaks with a parent and a child in each. The day was lightly breezy, which kept the bugs at bay, and we saw lots of birds, sharks, and spitting oysters. I’m a strong paddler, so I went ahead with one of the guides, Katie, who chatted happily with me about the challenges of being a woman guide as well as a working artist. I learned that Manatees love fresh water, and that it is illegal to spray them with hoses, even if they love it. I took 10 minutes to sketch the marsh before hopping into my car and driving to Orlando where I would stay with my Cousin Leah, and her family. The drive was uneventful. Day 4- Travel Journal Pages 158-163- Winter Park, FL Leah and I dropped the boys off at school and then she took me on a drive around Winter Park to see all the places where she grew up. We stopped for brunch and talked about our families, wandered around book stores and sampled artisan olive oils. We spent the rest of the morning looking at the exquisite Tiffany Glass collection at the Morse Museum of American Art before heading back to the apartment to work and unwind. I finished the painting from the marsh the day before and continued to reconnect with family I hadn’t seen in years. Days 5 to 8- Travel Journal Pages 164-167 Ft. Myers, FL I spent these days staying with my Great Aunt Mary, whom I had spent all of last October with after Hurricane Ian. In the spreadsheet of this trip that outlines the logistics of where I will be, and my expenses and income, I have a few stops that are meant as times to take a breath. Ft. Myers and time with Mary was one of those. We visited and talked about current events and the merits of digital art vs. traditional mediums. I worked at the public library on a design for a mural that would go in a grocery store in Kansas, I did laundry, and I went to the beach. There are plenty of things to do along the gulf coast, but I needed the moment to pause and reflect. Mary shared photos and letters to my Great Great Aunt Dit that had been hidden in a secret drawer in the Brower Desk, a handbuilt cherry behemoth that is passed through the family to anyone with the Brower name, and while the secrets I learned in the letters to Diddy are not mine to share, I feel honored to know them. When I painted on the beach overlooking the turquoise gulf, I took time to record the scene directly behind me as well. Ft. Myers is still devastated from Hurricane Ian, so the apartments behind me were gutted and crumbling. Construction buzzed as the buildings were being rebuilt, but the view looking West over the Gulf of Mexico offered no indication of the mess along the coast. I wonder what else I have forgotten about when I failed to record what was behind me Day 9- Travel Journal Pages 168-171- Mobile, AL The drive from Ft. Myers to Mobile, AL was uneventful except for a few miles of white knuckling through heavy rain as I drove north up I-75. The farther north I went, the more the interstate became rolling hills, and I got lost in undulating meditation as I listened to “Fiona and Jane” by Jean Chen Ho. I rolled into Mobile at around 5 pm and parked downtown to stretch my legs before heading to my next AirBnB. It was Easter Sunday, so everything was pretty quiet and deserted, just how I like my cities, and I was charmed by many of the old 2-story buildings draped in flowers and ornate iron work, punctuated by empty lots and store fronts. My cousin Ian loves Mobile, and referred to it as a dumpster full of gems. I think this is a useful description for a lot of American cities, and I wondered how the city changes when the cruise ships are in town, or when it wasn’t a significant Christian holiday. I’d like to go back sometime and see a concert and enjoy more time there. As it was, I enjoyed some decent beignets, and a quiet walk around the Spanish Plaza before turning in for the night at the Springhill Historic House and AirBnB. Day 10- Travel Journal Pages 172-176- Mississippi Gulf Coast and Drive to New Orleans, LA I pulled off the highway and stopped at Gulf Shores National Seashore. Before now, I had been to all 50 states, but I felt like Mississippi had been short changed since we only stopped for gas there when I drove the coast after high school, and I wanted to give it most of the day. The weather was gorgeous, so I painted the bayou from the fishing pier and listened to three fishermen talk shit and pull 30 pounders from the bay. One of the fishermen, a retired cop from Chicago, was really happy to talk to me while I worked, but he and his fellows tried to spook me when I told them I was headed to New Orleans later that day. They told me to pack a knife and a fake purse, and I took their warning with the grain of salt it deserved. Traveling alone is to be in a constant low level state of fight or flight, and I’m always baffled by the people (usually men) who seem to think I am unaware of the threats that go along with being a woman in this world. Granted, I am a white woman in a country that has been designed to protect me, but the dangers are real and I would be wise to recognize them. All this being said, if I allowed this to dictate every one of my actions, I’d never do anything, so I accept the concern of others with love because it is given with love. After painting, I moved on to Biloxi, where I ate shrimp and crawfish and sipped sweet tea before wandering around town and walking the beach where there were Wade-Ins during the Civil Rights era in protest of segregated beaches. I drove along the coast through the rest of Mississippi and noticed a Waffle House every 2 miles. The words of the fishermen weighed on me, so when I rolled into New Orleans around sunset to find my AirBnB in a neighborhood that was convenient to the French Quarter, but full of potholes the size of a Yugo, and historic houses in a wide range or repair, I allowed my unease to overwhelm me. Sometimes, I lean into being naive and ignorant, especially when I travel, and while the place I was staying was safe, bohemian, and charming, I worried that today was the day the bill for my nonchalance would come due and that I would find my car broken into. I spent the night and most of the next day sitting quietly in my room, listening to the occasional arguments from the neighbors and questioning myself. I resolved to not do anything at night and to take a Lyft the mile to Jackson Square, instead of walking. Days 11 and 12- Travel Journal Pages 177-183- New Orleans, LA, French Quarter and Garden District I got over my fear and had two lovely days in New Orleans. I did take a Lyft into town that afternoon and enjoyed walking the streets of the Quarter and eventually trying and failing to paint a jazz band in front of St. Louis Cathedral in Jackson Square. Most of the square was closed in preparation for French Quarter Fest that weekend, but I sat on a park bench and listened happily to the assorted brass instruments, saxophones, and drums as they played classic New Orleans jazz. It was times like these that I am reminded of why I seek the anonymity of music and the crowds that accompany it. The camaraderie of shared experience eased my nerves and I walked back to my AirBnB through Louis Armstrong Park, keeping my head on a swivel, but feeling much more relaxed. I ventured out again that night to see Hovvdy at the Toulouse Theater and enjoyed a serenade by Robert, my Lyft driver, all the way home. The next morning, I walked again to find the streetcar that would take me to the Garden District where I spent the day wandering and painting the old trees and exquisite houses and gardens. People barely batted an eye at me as I sat on the bumpy brick sidewalks and worked in my sketchbook, though plenty of tourists stopped to talk to me. I have one of those faces that invites conversations from strangers, and while many people were curious about me, most preferred to share their own stories, and I was happy to listen while I worked. Traveling/living like this is a bit strange because I don’t have unlimited funds to do whatever I like and I can’t listen to everyone who sends me a recommendation for what to do and where to eat. I’ve said it before, but this isn’t vacation, and I have to find a balance between what is a can’t miss experience and what is sustainable. The work of walking around, recording what I see, and sharing it is my job, but I can’t just move from place to place and skirt the edges of what makes a city special. This is where I wish I had a local guide to help sift through what is sensational and what is essential to a place. If left to my own devices, I don’t always opt for the unique experience and I fall into patterns of comfort. But that is another post for another time Days 13 to 15- Travel Journal Pages 184-186- Dallas, TX The next few days were spent with my friend from college, Natalie, and her husband, Mike. Unlike in NOLA, my friend was an excellent guide who helped curate my experience and cut down on a lot of the stress of deciding what to do with myself, and I was grateful to have the time with a person whose company feels natural no matter how much time has passed. Natalie lives on the 26th floor of an Art Deco building in the Central Business District and I found myself enjoying all of the details of the old skyscrapers and neon lights of the city. I would have never picked downtown on my own, since I gravitate to historic neighborhoods and rural places, so the experience was novel and gave me an appreciation for Dallas that was separate from its notorious traffic. Over the two days I was there, we visited the Dallas Museum of Art, ate excellent pizza at Partenope, breakfast tacos from the corner store, and wandered around the Bishop Arts District. I had Texas BBQ and saw Pedro the Lion perform in Deep Ellum. I visited with old friends. I didn’t write or draw anything. Again, visiting and experiencing the world is often at odds with recording it, but I will continue to endeavor to find the balance. Days 16 to 18- Travel Journal Pages 187-192- Amarillo, TX, to Las Vegas, NM After packing my car for an uneventful and windy drive to dusty Amarillo, Texas, in the Panhandle, I arrived at Mariposa Eco Village, just outside the city. I would stay in a canvas Tentrr “glamping” tent on rocky rangeland that I shared with some cows and a pack of coyotes. I had a queen bed and plenty of blankets, but once the sun went down, there wasn’t much to do except watch the stars and listen to an audiobook. The Eco Village was a nice surprise: remote, artsy, and quiet. I saw one truck, but apart from a few text messages from my host, I had the place to myself. I painted and posted a few pictures to social media and a friend suggested I check out Cadillac Ranch while I was in the area. Amarillo was meant to just be an overnight stop between Dallas and Las Vegas, New Mexico, so I had no plans to explore it. But when my friend in New Mexico told me she had an errand in Albuquerque that would keep her late, I needed to figure out how to mosey before the 3 hr drive. The wind had buffeted the tent relentlessly throughout the night, so I was up with the sunrise. I had a jalapeño bagel with the retirees at Roasters coffee, journaled, and thought about a friend from high school who died nearly 10 years ago. He was one of my first writing crushes. I had one in every writing course I’d had in college–something about talent and watching someone as they read out loud… it was pathological–I’d written him a postcard when he was in the hospital, not long before he died. Feeling morose, I found a nail salon that was open that early and got a manicure and ruminated on the act of killing time. This happens sometimes when I travel. If left to my own thoughts for too long, I start to get agitated. Everything feels heavy, deep and important. Journaling helps. Hands slick with lotion and still fragile shellac, I programmed Cadillac Ranch into Google Maps and drove 2 miles up the highway to the bizarre roadside attraction. Since 1974, people have been invited to park on the frontage road by I-40 and walk 500 yards out into a dusty field to spray paint the 10 vintage Cadillacs that have been partially buried by their hoods in the dirt. The experience is free, but you can buy stickers and a can of paint from a truck near the entrance and the nearly 50 years of built up paint has resulted in colorful and spongy masses that are reminiscent of cave formations. There’s a similar sight in Alliance, NE, called CarHenge, where vintage autos have been stacked in a parody of Stonehenge and I have to hand it to the hippies for creating something weird and wonderful that breaks up the monotony of the barren landscapes. I was charmed, so I went back to my car, grabbed my paints and Crazy Creek and sat there for 2 hours while people painted their names, favorite sports teams, and important dates on the cars. Plenty of people came to chat and share stories about their journeys while I worked. One woman was there to commemorate the 5 year anniversary of her son’s death, and again I thought of my friend. Sunburned, but pleased with my morning, I packed up and drove West. Part 5 is here.

We moved through the miles slowly some days and quickly during others. We met old friends from summer camp, distant relatives, great aunts, grandmothers and grandfathers. We snapped at each other, listened to audiobooks, and ate sunflower seeds. We visited our future college campuses and tried peach ice cream and powdered sugar-covered beignets. We got lost. We took wrong turns. Many of our wrong turns took us through city centers and were costly both in time and in money. Getting caught in traffic or having to pay unnecessary tolls was like instant karmic punishment for our lapses in attention. At these times, I tried to maintain confidence and morale as the navigator by calmly selecting alternate routes from the map in my lap. Occasionally, when we missed the appropriate junction or exit, I didn’t say anything and quietly chose another way rather than telling the driver to turn around. This bit me in the ass a couple of times, the worst one being when we accidentally crossed the Ben Franklin Bridge headed east from Philadelphia into New Jersey. We had meant to circle west around the city to where we would stay with a friend of Kate’s, but the detour into the wrong state forced us to backtrack. It was then that we learned that all bridges into Philadelphia are free to motorists leaving the city, but cost three dollars to cross if you intend to enter the city, and we were left to frantically dig around the car for quarters to pay the toll. Times like these made me feel as though my map had betrayed me. Modern GPS navigation devices have options that allow users to select routes which avoid tolls, and when wrong turns are taken the little dashboard mounted machine reconfigures its directions to calmly redirect the driver and get them back on track. Something in my core rebels against the idea of having a little box tell me where to go and I scoff at my friends who use their Garmins or Tom Toms for trips to the grocery store and other errands. The displays on satellite navigation systems show generic geometric shapes to indicate where you should go and lack the elegance that a map has. A map is both a tool and a piece of art, and offers a sturdier sense of place, so long as you are able to locate your position on it. This can be a daunting task but when you know where you are on a map, you feel grounded, as if you are part of a landscape that is translated perfectly between dimensions. Reliance on a digital landscape on a digital screen denies the user the chance to intuitively choose their own path based on their own sense of direction because they never truly understand where they are. Similarly, online navigation tools like MapQuest and Google Maps allow users to forego maps in favor of listed directions which tell them when to turn left and after what distance to merge right, but which ignore landmarks and other features characteristic to maps or verbal directions. But digital navigation tools continue to evolve to fit how users seek to use them. In 2010, Google unveiled Google Bike, which helps cyclists choose the easiest and safest route to their destination. Google Maps has further developed routes suited for pedestrians, which can be utilized in conjunction with their public transportation feature. No longer is a car required in order to get the most out of digital navigation. Most days, our atlas was enough, and we followed it up the Atlantic, through New England and finally to Vermont, our Northernmost latitude, at which point we turned around. Kate and Figgins left me in DC on the 4th of July and they continued west to Chicago. By the end of the summer, Kate moved to Idaho with her father before attending college at Albion in Michigan. Figgins moved to Arizona with her father before heading off to Smith. I went to American University in Washington DC and we all eventually transferred to different schools. Figgins was the first to leave. She moved back to Colorado after a semester at Smith. I gave American a full year before transferring to Washington University in St. Louis, but Kate almost made it through four years at Albion. She left at the beginning of her senior year, though she never told me why. I found out through a mutual friend that she’s back in Idaho. I hope she’s doing okay. Kate’s Subaru, Antonio, died last year. On facebook, we all mourned his passing. She still has Joanie, though, the dashboard hula dancer. Figgins still has the trip’s road atlas, though it is now four years out of date, and I still don’t have my driver’s license. What I do have now is a phone loaded with Google Earth. It politely asks me if it can use my current location and then accesses my GPS coordinates to show me my position from space. It zooms down through the virtual atmosphere, the image pixilating and then sharpening until it pauses and hovers 200 feet above the roof over my head. "You are here," it seems to tell me, like a big red dot on a map in an amusement park and I get a little vertigo from the picture resting in my palm. But I no longer fantasize about connecting the dots behind me. Where I have been is clear. So instead I hope and wait for the image in my hand to change from “You Are Here” to “Here Is Where You Will Go.” Note: Figgins uses they/them pronouns now, but chose to keep their previous pronouns in this piece to honor and acknowledge who they were then. Read Part 4 here. We left Zoe with her aunt on St. Simon’s Island in Georgia, and continued without her up the coast through Savannah and to the Outer Banks of North Carolina. Many road atlases mark scenic routes by tracing the appropriate roads with a dotted green line, and in the mountains of Colorado, most of the roads are marked this way. Figgins, who had lived all her life in the land-locked mountainous state, had confused the green dotted scenic route with the blue dashed line which delineates an inter-coastal waterway. It was her turn to navigate in North Carolina, and the atlas on her lap showed her the yellow line that she had drawn skipping across open ocean. We searched for the phantom dotted blue road to the islands, driving onto countless hazy peninsulas which thrust out into the Atlantic. After a few hours of driving in circles, we identified the error and located the ferry to Ocracoke Island and made it to our campsite in time to pitch our tents before dark. The Outer Banks of North Carolina loop east out into the Atlantic like a net cast out to catch tuna. Historically, the islands have undulated to and fro, but residential development has attempted to stabilize the sand, and developers struggle to reclaim land which is incessantly battered by wind and sea. The Wright Brothers selected the Outer Banks to attempt the first ever successful airplane flight because of the wind. Their flyer— the bizarre love child of a kite and a bicycle—flew more than a hundred feet over the dunes to where it landed with a thud in the sand. Ironically, there is no commercial airport on the Outer Banks today, so the only way to get there is by car or by boat and often, a combination of the two. The Outer Banks are also known for lighthouses. Each one is more than one hundred and fifty feet tall and features a black and white geometric pattern, the most eccentric of which is the Cape Lookout lighthouse which sports a diamond pattern and looks like a French harlequin. The Outer Banks’ has a few exceptions to the black and white rule, one of which being the stout white lighthouse on Ocracoke Island, which is less assuming than its northern cousins, but which I dragged my friends to, nonetheless. I had remembered this lighthouse from a trip to the islands years before when my family was traveling the opposite direction and I had wanted to see if it lived up to my memory as a landmark of my childhood. The Ocracoke Lighthouse is no longer in use, and like all of the Outer Banks lighthouses, is maintained by the National Park Service. Unlike the others, it does not have a gift shop, nor does it teem with tourists who wait in line for the chance to climb to the top. The Ocracoke lighthouse is chained shut and surrounded by low trees, sea oats, and tiny yellow butter cups. Most of the lighthouses are no longer in use, but in the United States, those that are operational are maintained by the Coast Guard. Traditional lighthouses housed families who were responsible for making sure the light functioned properly so that it could safely guide sailors past hazardous coastlines and through inland waterways to safe harbors. Each lighthouse served as a navigator and had a style unique to the seafaring culture which it protected. The rise of modern electronic navigation systems has made most traditional lighthouses obsolete which, in conjunction with erosion and encroaching seas, threatens their very existence. As a result, the coastal communities which were once protected by these illuminated sentinels now fight to protect and preserve them. One of the fiercest fights fought was for the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse. The lighthouse was commissioned by the U.S. government to protect an area that was known as the “Graveyard of the Atlantic” due to its notorious shipwreck-causing storms and hurricanes. Originally built in 1803 and rebuilt in 1870, the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse is the tallest lighthouse in the United States at nearly 200 feet, a height which is further emphasized by its trademark black and white spiral pattern that twists all the way to its top. The storms which were responsible for the lighthouse’s construction gnawed away at the shore and threatened to consume it, so in 1999 the National Park Service picked the lighthouse up and moved it, inch by inch, half a mile inland. By the time the three of us visited the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse, we had each begun to yearn for some personal space. The morning had been a rough one. I had stepped on a wasp and every step I took seemed to aggravate the burning itch that emanated from the angry red bump on the arch of my right foot. Packing up camp had been unpleasant and difficult in the gusting wind, and Kate had discovered her cell phone had fallen into the cooler full of melted ice and left to soak overnight. Tempers were short, so when we got there, we all went in separate directions. I got in line to climb to the top of the lighthouse, Kate wandered around looking for anywhere her sodden cell phone might receive a signal, and Figgins sat on top of a red picnic table in the pavilion and smoked one of her rationed cigarettes. When we met up again, we found that each of us had voicemail from the Colonel, politely ordering us to check in, or else he would be severely pissed off. Kate finally got through to him and tried to reason that cell coverage was spotty on the islands and that we were not purposefully trying to be difficult. I took the opportunity to call home only to learn that the Colonel had called my parents to see if they had heard from us. Figgins chose not to call anyone. When we got to the car we found that Joanie, the dashboard hula dancer, had wilted in the heat. The sun-baked plastic had softened causing her to lean forward precariously, bending at the knee like a flamingo. The adhesive that affixed her to the dash, threatened to give at any moment, so I pulled the ballpoint from the pages of my journal and wedged it against the AC vent to prop her up. Note: Figgins uses they/them pronouns now, but chose to keep their previous pronouns in this piece to honor and acknowledge who they were then. |

Addison GreenThe day-to-days of an Itinerant Illustrator Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed